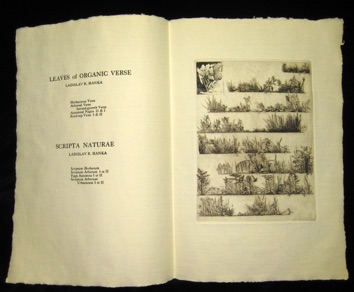

Scripta Naturae/

Leaves of Organic Verse

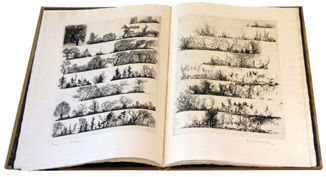

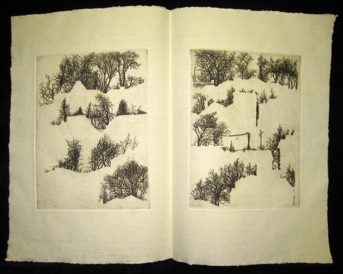

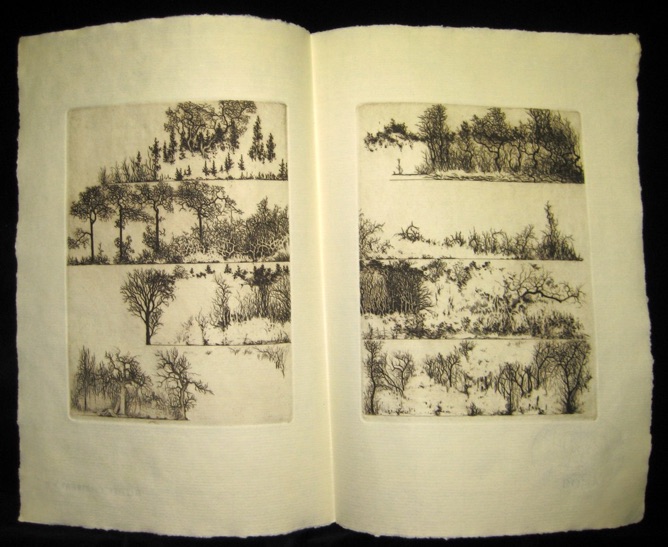

Scripta Naturae: 7 etched image plates

2 etched text plates

2 letter press pages

printed on several hand-made papers-

Roma, Velke Losiny Richard DeBass.

Prices vary:

individual prints - 350/plate

complete folio:

in unbound signatures: 2,500.00

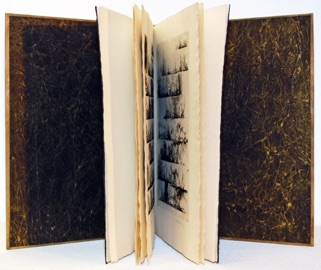

Bound in leather with slipcase by Vernon

Wiering: 3,000.00

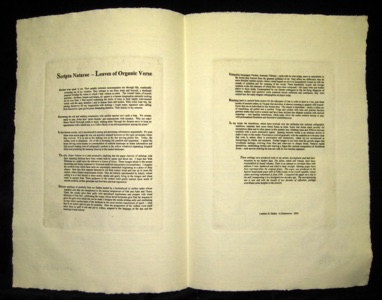

Scripta Naturae- Leaves of Organic Verse text

Binding by Jan Sobota

Scriptum arborum / Arboreal Script

Rooftop Verse/Scriptum arborum urbanarum

Binding by Jan Sobota

Title Page/ Scriptum herbarum

Binding by Jan Sobota

Scripta Naturae – Leaves of Organic Verse

With a bow to Walt Whitman, and his Leaves of Grass, in the title I use Scripta Naturae, a Latin possessive, with which I imply that the leaves, the pages of etchings - with their repeating horizons - have been written both by nature, and about her.

My images allude to the arcane knowledge and beauty contained in illumined medieval manuscripts - incunabula. The incunabula were crafted by adepts, gardeners of the written word I call them. Both their texts and mine are composed of symbols, symbols that originated in a place of deep silence. Here, they first separate themselves out from cosmic mind and rise up to meet the surface, where human consciousness dwells. The adepts, whose calling it is to recognize these coalescing forms and gently bring in the images and ideas ready to assume shape, nurture the seeds of nascent symbols, while they germinate and find their physical expression.

Delicate seedlings of symbolic form are further tended by a brotherhood of scribes under whose watchful care they are transplanted to the ancient scriptorium of Oak and Ashe and Thorn. There, the monks carve their quills with specialized implements and prepare with ritual ablutions of oak gall – celebrating the wasps, whose larval hormones give oak the impetus to grow the galls from which ink can be made. I imagine the monks arising before dawn to meditate on that which reaches back of the forebrain to the most ancient experiences of spirit – on what they’ll be called upon to pen for posterity. Then the progression of the written word itself takes form as quill is wetted and put to vellum, adapted to the language of the day and the meaning it must convey.

Unfamiliar languages - Tibetan, Persian, Aramaic, Chinese, each with its own script - affect me differently than do more familiar western scripts, whose accustomed visual impact on me is so immediately bound up with the meaning of the words, the well-known sounds of syllables. The foreign symbols, beautifully cryptic, evoke the elements from which they derived. Their scribes, our literate colleagues in the far-flung diasporas of wisdom seekers scattered across millennia and continents, borrowed their forms from the greatest syllabary of all - the trees and other plant forms native to those lands. Contemplated by adepts, they were coaxed into the diverse elegant orthographies we know today.

When I reach back to the oldest, primal brain sectors for the silhouette of oak in order to draw, I too join these monks of ancient orders. As I begin to grapple with branch-forms, I encounter the conundrum to be solved. Each tree is as individualized as any human body; their form must be condensed, twigs and rootlets; with time and practice must become gestural marks, stylized and abstract, symbols with emblematic meaning.

In my Scripta Naturae, the letterforms that evolved over the millennia into the great calligraphic traditions, maintain their more literal forms as trees. Some tree forms stand upright for forthright momentous ideas, while in other places in this esoteric text, climbing vines and pliant willows become symbols of a more flexible and yielding narrative.

The spacing between words, a device to make it easier on the reader, only came into general use in the Middle Ages. Earlier manuscripts were simply pages with unbroken lines of letters; words ran into one another and were broken arbitrarily when the scribe ran out of space at the end of a line: no hyphens, no rules of grammar, no punctuation. Spelling was up to the scribe - how he chose to sound out a word in his own accustomed way of speaking. It was up to the reader to make sense of these texts. Punctuation evolved only gradually, over the centuries, as it became clear that even in nature, there are familiar cadences as well as breaks and changes in rhythm, signs which we are accustomed to interpreting for clarity and emphasis.

As we move through the Scripta, we see the growth stages that woodlands undergo when they develop from fire-scarred openings and clear-cuts, slowly over decades and even centuries to become climax forest. Patterns repeat themselves, establishing rhythms that overlap with other rhythmic patterns, echoing the musical language of harmonics and counterpoint in a fugue-like textural concerto of deciduous forms – each species cleaving the heavens with its own familiar signature.