Remembering

Jan Bohuslav Sobota

by

Ladislav R. Haňka

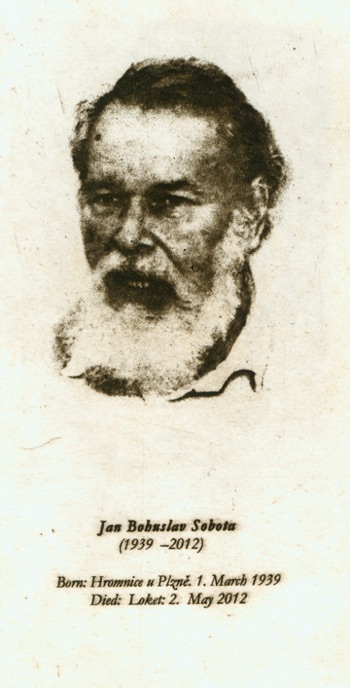

Jan Bohuslav Sobota died on May 2nd of 2012 and this is my remembrance of this fine man who was a friend and mentor to me. He was an exceptional bookbinder, teacher and promoter of the book arts, but also an exile who successfully returned home after years abroad.

He was a lover of fish and fishing. Thus the re-printing of these

etchings, depicting Spawned Salmon that accompany the text,

seems particularly fitting symbolism for remembering

Jan’s passage from this world

to the next.

Ladislav R. Haňka

Spawned Salmon

Each autumn, salmon return to the rivers of their birth – there to spawn and once again trigger a renewal of the eternal passion play. The millions of eggs and fry suffer severe losses at each stage of the life cycle – as they navigate the hazards of migration, life in the open sea and the ordeal of returning back upriver to the streams of their birth. When they do return, there isn’t room for all to spawn. Gravels, with just the right flow of fresh water running up through stones of the right size are but a tiny portion of the riverbed. The salmon must struggle past cities and sewer pipes, farms and irrigation systems, dams and turbines, fishermen and waterfalls – just to reach the streams of their birth.

Salmon that do eventually arrive at their destinations must once again compete – this time for mates and to fight for access to the precious and very limited gravels. There they encounter resident trout and bass – even sunfish, chubs and dace, all keyed into the increasingly plentiful and highly nutritious bounty of salmon eggs. These annoying little scavengers must continually be chased off as they sneak in to eat the eggs being laid – a diversion from the primary instinctual biological imperative, inexorably pushing the dying salmon to get on with the ancient rites of their kind, disgorging their precious seed into the gravels, while the current is sweeping much of it away and into a streambed already awash in salmon roe bouncing lazily down-stream and accumulating in eddies and behind logs

The profligate expenditure of life and extravagant wealth of biology is there everywhere to behold, as Death dances lightly among the gathering throngs of fish, picking and choosing from among them; who from their number shall successfully spawn and who shall just be food for the gathering predators and scavengers.

Spend a day in silence, walking among the spawning salmon, as they dig spawning redds, jockey for position and slash at competitors with those gaping, snaggletoothed, hooked jaws. You’ll never be the same. You’ll see the grotesque white fungus sprouting on their dark fins, skin sloughing off and the bright white bone of their skulls beginning to be exposed to view. They are already decomposing, still alive and desperate to spawn before their energy is spent and death inexorably overtakes them. It is a monstrous and beautiful thing to behold – far too big to be reduced to an aphorism or a moral.

Remembering Jan Bohuslav Sobota,

Stories, Speculations, Pronouncements,

Acknowledgements & Thoughts

on a Life in the Book arts

Jan Bohuslav Sobota has died, while half a world away; I was preparing these etchings of Spawned Salmon and dedicating them to Jan, the lover of fish. I imagined him playing with them as a kind of binder’s bonbon, but that was not to be. Like the salmon I’ve depicted here, Jan returned to the stream of his birth and has now finished out the cycle. He spent years out in the vast open ocean, competing with the big fish, but there came a day when some internal compass took him unerringly back to the place where a specific freshet of cool water enters the vast ocean – the one with its very own taste and mineral composition that arises from his own home watershed. Like a salmon, he too responded in the time-honored way. He turned upstream and swam and swam, until he arrived back home. For him it was Loket, a gem of Czech Gothic architecture, situated on an Oxbow of the River Ohře. There the flowing fresh waters surrounding him were balsam to Jan’s soul. His remaining years in Loket were meaningful, productive and happy. Jan completed this earthly incarnation at home in his own bed.

The book you hold in your hands has evolved from my simply giving these etchings a second life in book form, to my using them as a vehicle for honoring a friendship of three decades. Jan was a master of the bookbinder’s art and my collaborator in the book arts. He was also a lover of fish & fishing and thus, the book of Spawned Salmon makes a fitting eulogy for his life and passage.

In 1985, Jan and I had been corresponding for some months without ever meeting – all quite distant and correct. He assumed I was an elderly émigré from my dated and bookish Czech, rather than his junior by many years. I saw opportunity knocking and by hook or by crook, was going to meet him. There came a day, when my wife Jana and I just drove to Cleveland on a whim, arriving after dark to an empty house. Now what? Time on our idle hands, the devil’s playground beckoned and prodded us into scheming. It looked as if they were coming right back – dishes in the sink, coffee cream on the table. A regular Flying Dutchman. Eventually headlights rounded the corner. Coming down the block – looking a little wobbly…been drinking. The car pulls in. Some fiddling with car keys and coats. Car doors open and then from out in the dark they hear; “Citizen. Your papers please!” Oh my God! Fight or flight hormones! Full alert. Heart racing and then the realization sets in: This is America – is has to be a joke. We were invited in and killed a whole lot of beers into the wee hours. They recovered. We got off on the right foot.

A short bit of background on Jan Sobota to begin, but fear not; I’ll soon be spinning anecdotes and thoughts on books as art – celebrating Jan’s life of course, telling a few stories out of school, but also straying into the personal and speculative in search of the meaning to be derived from the life and death of a friend.

Jan’s father was a serious bibliophile and collector of fine books, who nurtured that same love of books in his son – an appreciation that steadily grew, until he was apprenticed to master bookbinder Karel Šilinger in Plzeň. Here Jan took to the arcane implements and luscious materials of the bindery as a duck to water. Making those skills fully his own, he then took them to another level of accomplishment. Šilinger would have been proud, for it is indeed a poor master, whose students do not surpass him.

Plzeň has long been a trading center and a hub of culture. Situated 90 km south-west of Prague at the confluence of four rivers, Plzeň is first recorded in writings from the tenth century. The city is well known by its German name of Pilsen and yes, Pilsener beers take their name from the original Plzeňský Prazdroj (Pilsener Urquelle in German), meaning ancient spring or primal source. Jan was a proud son of Plzeň and loved a good beer, so this is hardly beside the point. More to the point though, is that Plzeň is not just known for beer, but for all things bookish. Plzeň had a letterpress shop in 1468, the first in Bohemia and among the earliest in Europe – founded while Gutenberg was still alive. With the first printers of books, came the first bookbinderies and that brings us to the august lineage from which Jan derived, whose traditions he brought with him to America and which he generously

shared with us.

Jan took what his master gave him and never looked back. In the hands of a lesser artist that might have amounted to little more than a lifetime of repetitious work in a musty shop in the back street of industrial anywhere but instead, Jan breathed new life into an ancient craft. Thousands of books passed through Jan’s hands, from ninth century incunabula to books of the Gothic, Baroque and Renaissance time periods. Jan restored the entire Latin library of the city of Jachymov, consisting of 236 volumes as well as Johan Gutenberg’s Biblia Latina (1454-55). Over the course of a productive 73 years, he expanded the knowledge of which he was caretaker, and shared that wealth with countless others. He was awarded the Master of Fine Arts in book binding from the Academy of Applied Arts in Prague in 1969 and the honorific title; "Meister der Einbandkunst" in Germany in 1979.

His last big award, among many, is a posthumous lifetime achievement award from his colleagues at the American Guild of Book Workers in 2012. If this were Japan, he might have been designated a national treasure and been helped by all of society to preserve their cultural patrimony. But, this isn’t Japan. It is left to the private sector to navigate the economic hardships of conserving traditions and keeping our cultural values alive.

The pivotal event in Jan’s early life as a book artist was the posthumous retrospective exhibition of fellow Pilsener, Josef Váchal in 1969. Jan was thirty and well formed as a bookbinder, but here was a book artist who flew in the face of everything – the politics of the day of course, but especially the constrained view of what a book could be. Not just perversely contrarian though, Váchal was supremely inventive and original. It set the course for Jan and if you’ll stay with me, you’ll see that we’ll be returning to Váchal throughout this eulogy.

Jan learned well and he was determined to make a mark in the world. He did it all. He kept up his websites. He published catalogs. He exhibited maniacally. He documented everything. He kept contact with more people than anybody else even knows. He kept all those balls in the air and found time to bind – most every day. What a dynamo of energy! Jan Sobota will be remembered, but he paid for his successes in the many ways a person can turn unrelenting stress into chronic conditions, organ failures, cancer, hypertension and premature death.

What am I to take away from this? Is Jan’s example one to emulate – that with an unstinting work ethic, matched by Herculean efforts to promote the fruits of that labor, one can overcome a system stacked against us – or that we must be careful what we wish for? We live in a curiously perverse world, like that of the Red Queen in Alice Through the Looking Glass, (a favorite of Jan’s) where you must run as fast as you possibly can, just to stay in place. If you want to actually get anywhere, you must run twice as fast as that. Sound familiar?

Jan supported a family, sponsored workshops, exhibited widely, did conservation work on rare historic books, ran a gallery – and on it went. We loved him for it and enjoyed the events he and his wife Jarmila put on. Their hospitality was legendary, but I never saw them take a vacation that was not also a conference, workshop or book show. If Japan can afford to honor its artists, why do we not do so? Is it more important to have munitions factories in every senator’s district, before any precious taxpayer’s dollars can be diverted to our common heritage? Does culture fly that far below the radar? I tend to go on and on about these things, but Jan’s usual answer was, that a skilled person willing to get off his duff and roll up his sleeves, will always get by.

Jan did more than just get by. He managed to duck the day job. That blessed day arrived at an age when others receive pensions, but self-employed artists aren’t included in that deal. The victory was meaningful. Conservation work had been paying the bills, but Jan needed to make better use of the years he had left. He accepted less and less outside work and dedicated more time to the art for which he wanted to be remembered. Saturday’s Book Arts Gallery in Loket was Jan’s bid for artistic freedom and that is where he did eventually win that uneven financial contest. He did so without anybody else losing. Instead, Jan brought others along with him.

What Jan did for contemporary bookbinding, was to act as a bridge between the traditionally trained masters of the past and innovators of the present. That is true for every generation of apprentices as they mature to mastery, but Jan’s arrival in North America came at a time when all was in flux and traditional skills at a low ebb. He was well situated to make use of that unique moment, for he was not just an excellent craftsman, but also a well-read synthetic thinker, with the agenda of an artist. He hit the ground running and kept moving.

America was a great place to be a book artist in the early 1980’s precisely because it was an active zone of hybridization and hotbed of creativity. The dusty and moribund sides of the book arts were nearly dead and buried and the new was just arising, like a Phoenix from its ashes. Neither fish nor fowl, but more like a Chimera; the book arts were now becoming something brand spanking new. There were no longer rules or standards. It was all nebulous and coalescing.

An instructive contrast to the anything-goes US scene was the icy reception I got when I showed a wooden box containing loose sheets of poetry and etchings to a Prague publisher. He cast the work a cursory glance and sniffed that it was too bad I had put such effort into something that is without value. “It is nothing – neither a proper book nor a broadside. I don’t see why you bother.” Wow!

Shock therapy followed by ice water immersion. That’ll teach me to try something innovative! American’s tend to be criticized for being Pollyannas. Everything is just so wonderful and everybody so creative, but suspending judgment long enough to actually look at some artwork and then giving it a chance isn’t so bankrupt, is it?

Neither Jan nor I had much interest in the book-like objects that often sneak into the museums as book arts – the carved and glued together things that sorta, kinda have a bookish aspect to them – rough-looking – perhaps chain-sawed Oaken boards or granite slabs, slathered in tar and lashed together with jute; but lacking text. No pictures. No pages to flip through. “Book art” for those who don’t really like books. And non-adhesive bindings? OK for starters. Perhaps right for those who shouldn’t have sharp objects, for fear of hurting themselves.

We were both more hide-bound traditionalists than that. Give us books that are meant to be opened and read, bound in animal hides with slipcases, but please do it in ways we haven’t seen done a thousand times before. Jan honored his masters and the tradition from which he came. His standards were high, but he was also far from a hopeless conservative. He embraced copiers, Mylar and fake vegetal parchments as quickly as the next guy. You bet!

As an artist, Jan had a compelling vision – subtle though it may have been. That vision was about innovation and creativity within the context of an historical tradition. His art form was still a craft that needed to meet technical standards and serve a well-understood purpose and only then could it become a vehicle for innovation. In the following pages I hope by way of anecdote and example to peel back some of the layers of that onion that was Jan Sobota and thus arrive at a sense of the core artistic vision that informed his bindery work.

When Jan’s books went beyond function, conservation or decoration, they were subtle statements about binding and the place of books, knowledge and art, as well as statements about the dignity inhering in the handcrafted - with a good dose humor. His books may not appear to be that self-referential on their surface, because they are indeed decorative and clearly reflect on their immediate and obvious content. A closer look will, however, reward the effort invested, for Jan was a serious artist and the content is indeed there to be found.

Jan was a magnificent repository of historical book learning. Apprenticing in Prague and Plzeň, he handled many a rare and ancient tome. It came out in his fanciful borrowing from historic styles of binding. Jan had eviscerated medieval books and repaired cracking, moldy parchments. He knew them as a surgeon knows the human body – as a butcher knows meat. He employed slipcases, bags, satchels and boxes that took as their point of departure real historical techniques and then he innovated – riffed on them and ran with them. It takes Jan’s expertise and love of history to pull that off and not end up with an undisciplined, syncretistic mess.

There are others who know their conservation and those, whose scientific contributions are far greater, but few of them are also artists at heart. Jan tread the razor’s edge between art and craft on one hand and between science and craft on the other. He did so with brinksmanship worthy of a diplomat. The binding was many things – protection, containment, framing device – even decoration. That binding could embellish or accent the writing, but the line it could not cross, was to diminish or detract from the contents.

Jan’s design bindings were where he broke new ground and furthered his own tradition. Jan the diplomat, balancing art versus craft; Jan the conservation master; Jan the historic font of knowledge; they all got to use books as a vehicle for pushing at the bounds of the discipline. He created extravagant containment and presentation devices – slipcases gone mad, even to the extent of dwarfing the book, buried like a treasure somewhere deep within. Here is where Jan moved the technical aspects of his field forward. He came up with solutions to conundrums that confound anybody working with living materials that expand and contract with changing temperature and humidity – materials that are furthermore subject to rot or vermin infestation. Look closely and

you’ll see that even when he has seemingly gone over the top, in Jan’s capable hands, these devices always referred back to the text and made sense in their dimensional relations. Deformations were intentional and worked to the greater good of the whole book.

It can sound so pedestrian, these eternal compromises between art and craft, yet what Jan represented was not at all common. Limitation can be galling or it can lead one to a disciplined way of working that far surpasses mere thrashing about in an undisciplined faux-liberty. Take fauve paintings. Are they more interesting for their wild use of every color in the paint box? Are the paintings of Caravaggio or Rembrandt dull because of their limited palettes? Context is everything.

There is an inflection point at which exceptional craft begins to make the transition to art and it is closely associated with surmounting the limitations inhering to the discipline. This is what you’ll see in a Sobota binding – exceptional attention paid to context and relationships, using materials and technical means that do indeed function and last. Jan was the equal of any ego-driven self-promoter, but a lot easier to stomach. He had well-founded ideas on books and art, but rather than pompously pounding a lectern and haranguing all the poor fools with his ever so important, updated truth of the day, he just let the work speak for him.

Jan may have been a modest man, but he wasn’t without aspirations. He knew his work was valuable and documented it fastidiously – confident that it would be last. Those well-bound volumes that document Jan’s art sit on their bookshelf in Loket – a long shelf with one bound volume for each year of his professional life. There they patiently await the proper curator, who will see past the dust and realize what lies hidden within. When that happens, Jan’s work here will have reached posterity and been completed.

Visiting with Jan in his workshop you quickly realized, that he did what a professional must, but ultimately, he just loved messing about with books. I think of dear old Ratty, in “The Wind in the Willows”, who went on dreamily about there being nothing half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats. Simply messing…messing…about…in boats… Jan got lost in the leathers and glues and papers. Perched there on his stool amid the piles of books; he was a satisfied creature, just pondering over some complex conundrum of binding. Messing….

In 1982, Jan took his family into exile, first to Switzerland and later to America. Sponsored by the Rowfant Club of bibliophiles in Cleveland, Jan had immediate employment at the book conservation labs of Case Western Reserve University, a club of well-heeled book lovers at his back and a chance to start over. There were other opportunities and eventually another excellent position at Southern Methodist University as well as a chance to be an active participant in the nascent American book arts movement. Jan and Jarmila felt welcome wherever they went, but they weren’t kids anymore. They watched their children adapt, but they remained foreigners until the day they moved back home again – until they landed in Loket. There it had to stop. They took a stand; built a shop; started a gallery; then a book binding museum; did it all from the parapets of their bastion at Loket. “ We only leave here feet first, on a plank!”

A curiously protean hybrid of artist and craftsman, ancient and modern, one cannot think of Jan without seeing an unabashed Czech patriot in a foreign land. There was, however, nothing about his nationalism that demeaned anybody else’s traditions or origins. He survived both Nazis and Communists, yet that adversity didn’t embitter him. He was kind and circumspect in how he spoke, but no fool. Jan also had a lot to say about the US, so let’s get back to that American chapter in the life of Jan Sobota. He liked it here – they both did. Jan and Jarmila kept returning to teach workshops, restore books, exhibit and ultimately to keep revisiting the many friends they’d made here in the states. Jan was an astute observer and his experience of America contained contrasts that spoke volumes. You want some examples – right? I have some.

Early on in their stay in Cleveland, the Sobotas experienced the quintessential American disaster. They became financially destitute when Jan developed cancer. He survived, but the story doesn’t end there. It becomes an epic saga. They came to understand intimately that America is indeed a society where neighbors rally and help each other just like in the movies with pioneers in Conestoga wagons moving west. This view of America isn’t just a half-baked Hollywood fabrication of frontier grit and aw shucks, good folks. People they hardly knew appeared with casseroles, left meat loaves on the porch, lent them money and took up collections. These folks were a profound blessing to a family facing some truly rough sailing – a Godsend. The Sobotas also discovered that, America’s pioneer spirit not-withstanding, kind neighbors couldn’t stop them from slipping into a crushing psychic debtor's prison over a health crisis. That too, was real. The light at the end of the tunnel was pretty dim – more like the view from the bottom of a deep well.

Now comes the Sobota story I most love telling. Jan had staggering medical debts, a colostomy and a family to support. He took on more conservation work, among which was an old book with crumbling boards. Inside the leather covers, Jan found an odd mass of stuck-together papers, which he soaked and carefully teased apart. These scraps turned out to be a deck of medieval playing cards - the second oldest such cards known. Some medieval binder had recycled a greasy old deck of worn-out cards and made boards of them. Jan restored the cards and sold them for enough to cover his medical expenses. Few people would have cast a second glance at that glued-up mess of moldering old papers before pitching it, nor would they have recognized what they had in hand or known how to restore or sell it. God helps those who roll up their sleeves and get on with it. Back home, their Czech neighbors would have envied them and accused them of theft or worse, but people here seemed to be pleased as punch to see them prosper – genuinely happy for them.

Even after their medical debts were retired, money was still an issue for a family of immigrants with three kids – two with special needs. It was no joke. They say it takes a village to raise a child, but where is that village, when you aren't a local whose roots go way back? Where’s the village in a Dallas suburb, where everybody is mobile and nobody remembers what the neighborhood looked like ten years ago? At one point the Sobotas responded to the seductions of a high-pressure sales pitch. They crashed with my wife Jana and me in Kalamazoo, while taking the “orientation course”nearby. Day by day we watched them both become indoctrinated and groomed to invade their Czech homeland with cleaning products and a pyramid scheme. They left in a haze of get-rich-quick excitement, but in a week their freshly laundered, starched and ironed brains began to soften and wrinkle. They were awakening to an avarice hangover. Jan, the master filter of propaganda and Jarmila, the astute psychologist, finally realized that they had been thoroughly buffaloed. They bashfully admitted their foolishness and went back to making beautiful books – and their American friends were so relieved to see them regain their sanity.

Later on, when they were living in Texas, the massacre at Waco opened Jan’s eyes to yet another difficult side of his adopted home. That smallish incident within the parade of American fringe politics elicited an insanely violent level of suppression. They didn’t even have the sense to hush it up, but broadcast it live over national TV. Jan sat glued to the tube, as this travesty of justice was unfolding and with a ghastly inevitability plodded on to its stupidly brutal end. That massacre left a far larger mark on Jan than one might expect. He’d been witness to far worse, but he didn’t expect it of the US. American society was becoming far more complex in its highs and lows and Jan was getting to know us in more nuanced ways.

Jan cast a broad net and knew many people across Europe and North America. Each of us would have different Sobota stories to tell. What makes me uniquely situated to print my stories about Jan is that I owe him. I also have a press and the means to do so. Flippant yes, but also direct and to the point. We were collaborators. He bound at least thirty of my books – some in complete editions. We exhibited those books together. I need to bear witness.

I’ve traversed the world of post-war Czech émigrés in which Jan functioned. I’ve lived for several years in the Czech homeland, but mostly outside. From Vienna and Toronto, to Chicago and Cleveland, I know the places where Czech culture has taken root, whenever life back home became hard and people forced into exile. I am also second generation and thus as much American as Czech – a hard balance to strike, but also an interesting position from which to observe and report. Finally, I am bilingual in Czech and English and have translated for Jan through the decades of his peregrinations. I can confidently report back to my English reader, that Jan would only grow in stature for you, if you could have fully understood the subtlety of his thoughts in his own maternal tongue.

Jan was a mentor to me in my early years as an artist. That relationship then evolved comfortably into friendship, as we became collaborators and colleagues, on into the age of graying beards – and of course, long past the day when youthful folly is a credible excuse for any short-comings. Now that I’ve outlived Jan, I may still work to meet his standards, but my books will no longer be made for him to bind. Those days have been reduced to sentimental reflections.

So then, what now? For whom do we make our art? For ourselves? Sure. But, that has its limitations, if the works are to be exiled to the dark recesses of a flat file and never feel the caress of a reader’s hand or the gaze of a human eye. We certainly create for friends, colleagues, teachers and intimates, hoping to measure up to their expectations – perhaps for posterity. You take stock at these inflection points and look for reasons to continue. It sounds so simple. People die all the time. You take time to grieve and then pick yourself up by your bootstraps (by God – get a grip) and get on with it (Rome wasn’t built in a day you know). But, there are so precious few friends whose approval is informed enough to be meaningful. Nobody gets more than a handful. When any one of those critical few die, all bets are off.

So why do I make books? I certainly made them for Jan, but it didn’t begin there. I was introduced to books as art by my maternal grandfather, Richard Neugebauer. A local patriot of the Czech-Moravian Highlands, amateur historian, decorated war-veteran, collector of folklore and book lover, he saw the potential in his American grandson – the one who was always drawing pictures and interested in his grandpa’s stories – the one he would see just a few key times in life. He took me to the Museum of the Book in Ždár nad Sázavou, and it was here that the books of Josef Váchal set a fire under me that eventually led to Jan Sobota. So, please bear with some pages of digression, as I tell my stories. You’ll see that they have a way of coming back around to Jan Sobota and the book arts.

In 1979, I apprenticed with Jindra Schmidt, an engraver of stamps and currency, living in Prague. The old bachelor belonged to an extended family that extended I knew not quite how far. That got me in the door perhaps, but

equally important as the iffy blood spoor, was my mother’s picture on a Czech postage stamp. Issued in 1938 as a fund-raiser for a children’s relief effort, it read; “měj ůctu k duši dítěte – have respect for the soul of a child”.

Depicted you’ll see the universally respected first Czech president, Tomáš G. Masaryk – and the cute little girl with a bouquet of flowers, is my mother Eva, at the age of three. This widely beloved stamp was re-issued in 2000 and mother continues to receive philatelic fan mail to this day. The engraving was masterfully done by Schmidt’s long-dead colleague, Bohumil Heinz (1894-1940). And so he pulled some string deep within the apparatus of the socialist workers republic and took in the American son of the girl on the stamp, to show me a thing or two about engraving.

Mr. Schmidt’s income from the federal mint far exceeded anybody else’s in the extended family and supported a network of cars, cottages and rent-controlled flats. “Strejček”, or little uncle as they all called him, just engraved all day long and came down for meals. They washed his laundry and drove him around to his appointments. They tended him like a hothouse flower and called in the doctors at the first sign of a sniffle on the horizon. They were also selling off his things. Bit by bit, the many prints, signed stamps and engraved pieces of steel were transformed – into transmissions, verandas, sump pumps and chimneys. Memorabilia left by the many artists with whom Mr. Schmidt had worked was signed with warm dedications to him and thus worth real money to collectors. Those items too, kept trickling out the door, until there came a sad, sad day, when the golden eggs were all gone. The writing was on the wall. Strejček was still working, but it was all coming to an inevitable end, as he grew shaky of hand and hard of seeing. He engraved his last stamp in 1982 at the age of 85 and died in 1984.

Schmidt had engraved stamps for Bulgaria, Iraq, Ethiopia, Albania, Guinea, Vietnam and Libya. He engraved currency for both Czechoslovak Republics, the Nazi protectorate, Terezin/Thersienstadt concentration camp, Slovakia, Poland, Cuba, Romania and others.

In 1992, Jindra Schmidt was honored for his contributions and depicted on the last stamp of a united Czechoslovakia, before it split into Czech and Slovak republics – a fitting tribute.

Mr. Schmidt, as he preferred to be called, was a man of conservative demeanor who preferred polite and reserved forms of speech and address. He was a holdover from the Austro-Hungarian Empire – a humble craftsman of regular habits. He had a single beer a day, at the same pub in the same company. He seemed to know only people around the mint and artists whose designs he engraved. His stories about working with well-known artists were cool, but I never actually got to meet them. They were mostly deceased. It was an odd apprenticeship without much structure, but hosting Eva’s son fit into a byzantine web of extended blood relations and the honoring of decades long loyalties and wartime debts, which I’ll never fully understand, but for which I am grateful.

Unlike most children of immigrants, my destiny remained connected to that of my parents’ homeland. Improbable-sounding notions morphed into events with a sense of inevitability about them. I needed to experience Prague and so my paperwork just slipped through the cracks of the system. They didn’t so much allow me to stay as, “not my job” bureaucrats, neglected to deport

me. While visiting their unassuming engraver and extending my tourist visa 30 days at a time, I was quietly becoming qualified for life as a counterfeiter – a vocation within which, one is set for life, however it may eventually turn out. If only making money weren’t such a dismal way to spend one’s days. The state security apparatus was surely aware of my presence, but if they kept tabs on me, I never knew. Perhaps there were simply better prospects upon whom to work their seductions and entrapments. Perhaps I had a squad of guardian angels working overtime.

My vocation as artist clarified itself in Prague while learning the increasingly obsolete skills of steel engraving. I could see how few stamps worldwide were still being made by skillful engravers and also came to the realization that Strejček knew them all. They were ancient and dying out. Even Mr. Schmidt suggested that I draw very well and need not interpret somebody else’s art, as he does. So instead of engraving microscopic lines all the livelong day, while hunched over and straining through a jeweler’s loupe, I began visiting the galleries and especially the National Museum’s rare book collection. There I re-discovered the books of Josef Váchal. In the print study room, I was handed his life’s work to peruse to my heart’s content. I ate it up!

Váchal became my model for what a book could be. The beauty of these idiosyncratic hand-made tomes with their rough-hewn inventive letterforms, unique to each book and hand-cast, generously interspersed with multi-colored woodcuts and bound in full-leathers caught my imagination as books never had before. They leaned upon traditional Czech folklore with a maniacal inventiveness – full of diabolic bestiaries and gruesomely delicious skullduggery.

Váchal had it all. Demonic encyclopedias followed upon obscure astrological diaries and treatises on the spiritual life of a dog, sniffing at fireplugs. In “The Plague on Korčula”, Black Death was personified and followed on its rounds, visiting the merchants and tradesmen on the Adriatic Isle of Korčula. Then there were The Witches of Holešovice; or the Prisoner in the Bolshevik’s Castle. It was positively liberating. A naturalist and spiritualist, lover of mumbo jumbo, transcendentalist and fisherman, I took the bait and the hook was set solidly into bone. Before I knew it, I was gaffed and gasping on the bank. I’ve been doing battle with printer’s imps ever since.

Váchal was an opinionated curmudgeon and did it all himself. He never got on well with Commies, Nazis or anybody else with a political agenda or an opinion that crossed his own – which included most everybody. He lived off alone, making his books and decrying environmental ruin long before that was popular. He is said to have been a Theosopher, but the piss and vinegar in his veins don’t really fit that image. In one book the colophon reads: I Josef Váchal have made this book in a single copy as a thorn in the eye of bibliophiles. Wow. I like book collectors, but you gotta admire his independence.

I went on Váchal pilgrimage. I discovered the National Memorial Collection of the Written Word, went back to the Ždár Museum of the Book, back to the National Museum’s rare book collection and searched the side streets of Litmyšl for the Portmoneum, where the Váchal museum is now located. Litmyšl is a medieval architectural treasure in northern Moravia and situated along the ancient trade route connecting Rome and the orient to the Baltic Ocean- where ancient traders in gold and salt traveled with armed escorts by day and stayed in fortified inns by night. The route is already mentioned by Kosmas in 981. The Portmoneum, though, is a modest family home, once owned by art collector Josef Portmon. From 1920 till 1924, Váchal covered nearly the entire interior of the house with demons, serpents and monsters. Compulsive as any book Váchal ever made, the Portmoneum was the final nail. I was ready to go off and be the Váchal of Kalamazoo.

My first book was indeed, modeled after Váchal, even to the extent of its diabolical subject matter. Entitled “Čertův Kámen” (Devils’ Rock), the volume contained folk tales collected from across the Czech-Moravian highlands and set to verse by my grandfather, accompanied by my own rough-hewn wood engravings. Think of the stories as a Czech version of The Grimm fairy tales, with a bit of “The Devil and Daniel Webster” thrown in – clever villagers outsmarting the devil at his own game with some potty humor, political innuendo and the usual range of human peccadilloes. “Devils’ Rock” was glowingly reviewed in Fine Print, but just one person responded. Jan Sobota, the newly arrived guest of the Rowfant Club in Cleveland. He understood immediately what a treasure this material could turn out to be. He asked for a copy of my grandfather’s devils and this first book set the course for a 27-year collaboration.

Jan showed me a great deal in the following years about the tradition of books as the meeting place of art, craft and ideas – where printmaking intergrades seamlessly with the worlds of language, typography and illustration. It was Jan who introduced me to that world of fine leather bindings and the historical binders art; with all its clasps and hasps; locks & buckles; bags & boxes; peculiar adornment & containment schemes for all the beautiful breviaries, songbooks and prayer books. Medieval incunabula and libri catenati (books in chains) come to mind; Tibetan palm leaf books; Mayan codices. It's our history – knowledge and experience, made compact enough to be portable. Does it get much better?

One can like these things just fine and admire them from an uncomprehending distance, or you can become engaged. For me, that engagement came by way of Jan. He lured me in and had me hooked in no time. He proceeded to reel me in masterfully, careful not to horse me too hard or give me too much slack and lose me. He gave me a show at his gallery and showed me exceptional bindings (ones that obviously far surpassed my own). He put unique historic rarities in my hands, which I then saw him fearlessly pull apart to replace boards and re-sew. He never tried to make me over into a binder, but worked with my proclivities and strengths. He wanted to see the printmaker in me come to full fruition and I wanted to be worthy of his attentions.

The book you hold was to have been a simple reprint of the Spawned Salmon – something fun for Jan to work his magic upon. But Jan will bind my books no more. He died the day I was composing a colophon for the Spawned Salmon with words of praise for his life’s work. He went to bed, leaving partially completed books on his bench and never woke up. That mourning, far across the Atlantic, in Michigan, it was still dark when I awoke. Unable to sleep, I began collating pages and editing this colophon. Sometimes I see the dead. My grandfather, Richard Neugebauer, appeared to me shortly after he died. I hadn’t yet received notice of his passing, but he seemed to be making the rounds before moving on – just looking in on me one last time. When Jan died, something was not right with my world – but I knew not what. The text of that original colophon has been expanding ever since; as my memories of Jan expand to ever more pages; as I pause to consider this unlikely alliance and why I make these laborious books for such a limited audience and indeed; as I re-consider my purposes for continuing with this capricious folly.

Like myself, Jan grew up fishing. For him, it wasn’t the mysterious salmon runs of the Great Lakes or the esoteric ritual of fly-fishing for trout on the fabled “Holy Waters” of the Au Sable River. He grew up poaching trout in the countryside near Plzeň. No sportsman with fancy fishing gear, he was just a village kid without permits or scruples about that sort of thing. An efficient little predator, with one purpose in mind, he snaked them out by hand, with the infinite patience that only a child can bring to bear on such a crime of passion. He waded around the ice-cold streams barefoot and felt around under the rocks beneath the stream bank, until he found a trout. It's a timeless pursuit, getting your hands down under its belly, ever so gently, a millimeter at a time, until the warmth of the human hand lulls the trout into torpor and those patient little fingers can keep on creeping right up into its gills. Then, in a crucial moment, you squeeze and snatch. It was an experience which neither of us ever quite outgrew – a couple of bad boys connecting at the level of hooks, books and misdemeanors.

We never actually fished together. Jan wasn’t that healthy and he never had time – always at work on a book, or thinking about books, planning a binding or catching up on work that had been promised months ago. There were family obligations and never a convenient time to take half the day off. Never the less, some of our best collaborations were indeed books on fish and fishing. They came from a common experience laden with the emotional content that is the underpinning of all good art –the real goods that tap into the collective unconscious and feed our souls. We egged each other on until there came a day when Jan made a housing for one of my books in the form of a pike. This wasn’t just any old pike, but one for the record books

Jan’s pike book sculpture was bigger than Jan himself – a full two meters long. That was one magnificent and masterful piece of bookbinder’s art, employing all the tricks and materials the old binder had up his sleeve. And he did keep some fine skins up his sleeve too – eels & snakes, toads & frogs, carp & stingrays – nothing but the best – or at least, the most enticing.

Our shared love of fish and fishing also extended to their consumption –

for Jan was not the sporting kind of guy to just catch and release them. What would be the point of releasing a scrumptious fish you’d just spent hours catching – except perhaps after digestion had taken its course? Not a chance. Jan grew corpulent because he loved to eat. That was especially the case for all things slippery and scaly, whether scorched on

a stick at fireside and consumed with a warm beer or eaten from fine porcelain with lightly steamed asparagus and a well-chilled Riesling. I’ll think of Jan with every scorched little Brook Trout I ever fry up at streamside.

Nice sentimental reminiscences, but there is still the matter of getting the work accomplished and out before the public, organizing exhibitions, printing catalogs and paying for transatlantic flights. Jan was good at that side of things too and unlike most artists, he was actually capable of making a good idea come to fruition in real time and three-dimensional space, to get the press releases out in time, reviewers on board, catalogs printed and not to lose his shirt in the process.

Exhibiting at the National Museum in Prague was a culmination for us both. This show was modeled after “50 x 25”, a highly successful show that Jan curated in 1995 at the Bridwell Library in Dallas. He’d asked 25 colleagues from the Guild of Book Workers to bind my books – two each. One for themselves and one for me. They enjoyed complete artistic freedom. All fifty were shown in Dallas and then those belonging to either Jan or me were circulated to other venues. That show was purchased whole by Special Collections at Western Michigan University and constitutes the largest collection of Sobota bindings and the most complete archive of my work.

The exhibit in Prague, at the National Museum on Wenceslaus Square in 2007, was entitled: The Books of Ladislav Haňka; in unique design bindings. The show centered on a selection of my books in the hands of 56 invited European bookbinders. Also featured, were books of mine, that Jan had been binding since 1985 and a catalogue (with English and German summaries). That portion of the show belonging to me or to Jan has been shown in several Czech museums since.

None of this would ever have happened without Jan’s tenacity. He grabbed hold like a bulldog and stayed with it until all permissions were granted, every bureaucrat signed off; payments from the underwriters, advertisers and participants were collected; the many ruffled egos assuaged; strident voices heard out; every concern answered; all the documentation and signage collected from procrastinating artists; all pages of the catalog collated; the text proofed, typos busted, corrections made and everything re-proofed again. This too, is a picture of who Jan was and why he engendered such loyalty. He organized a show that was certainly good for his own legacy, but he put my work in front of a large public that would never have seen it otherwise and he brought along a great many of his colleagues and former students as well. He shared his good fortune and furthered the interests of others. And what a show it was. The wine flowed freely. Dignitaries spoke and spoke and then spoke some more, while liveried trumpeters in renaissance garb and powdered wigs blew their horns and pretty maidens with long plaited tresses in perfect period dress delivered exquisite hors-d’oeuvres on silver platters. My sister, wife and mother all flew in for the event. Aunts, uncles and long lost cousins appeared. Everything was oh-so-tasteful, memorably theatrical and just so.

The Prague show was reconfigured and curated by Jan‘s longtime friend, Ilja Šedo, for exhibition at the West Bohemian Museum in Plzeň. This show was Jan‘s triumphant return to his own home town on the occasion of his 70th birthday, in 2009. The Czech Society of Bookbinders recognized Jan (a founding member) with the Karel Šilinger lifetime achievement award. Entitled: „From Váchal to Haňka; bibliophilic imprints by Josef Váchal and Ladislav Haňka in the bindings of design binders“, the show might as well have included the byline; “by way of Jan Bohuslav Sobota“. And of course, Váchal was there as a centerpiece. Jan managed to score a small stash of unbound copies of „Malíř na Frontě“ (Painter on the Front Lines) in which Váchal penned and illustrated his sardonic memoirs from the First World War in Italy and

Russia. Jan allowed several binders to have their way with it – amo boxes for slipcases with shell casings for hinges and so forth. Jan bound a rare copy of Váchal’s re-edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s, Raven. I was in good company – you bet; hang together, lest we hang separately.

Most of the pomp and ceremony stayed behind in Prague, with the seat of the government. This next incarnation of our exhibit in Plzeň was all just a bit more prosaic and provincial. The wine wasn‘t as expensive, the ceilings as high or the speakers as impressively garrulous, but the heart was there. Jan was home among his own people, surrounded by their love. The museum honored not just Jan Sobota that day, the proud son of Plzeň, but also Jan’s lineage – his master, Karel Šilinger and Josef Váchal, some of the finest Pilseners ever to pop a beer, cast some type, bind a book or fry a fish. For me, the added pleasure was seeing some of the books open and a selection of their contents displayed – my contribution too, was finally being seen.

So then: Books as an art form: What are they exactly? Is it the binding we consider and exhibit – or is the binding there to conserve a text, which is ultimately the point? With a finely produced monograph of 18th century botanicals or a book of original signed prints, perhaps it would be the illustrations that are the primary focus. Book arts are notoriously vexing to exhibit, because they are all of the above and made to be handled. A book is so much more than the sum of its parts – and yet each of us tends to have our own bailiwick in which we shine and to which we look first.

Quite predictably, I like seeing the kind of work I do honored – the wood engravings and etchings made to shine in the context of crisply printed type and an excellent binding. A show of innovative bindings is enjoyable, but leaves me hungry for the meat of it all – for the complete book. I want to open it up and feel the papers, see the typography – and examine the illustrations.

I’ve heard printmakers lament that the surest way to devalue prints is to add excellent poetry, sensitive typography and a bang-up binding – and then live to see the whole thing sell for half the price of just the unbound prints. There are also binders to whom everything else is merely the text block, who care little if it is an offset trade edition or a book made by hand. You could lose heart. Jan, however, treated text and artwork as sacred. His bindings were a complement that did not distract from the content. That’s some good brinkmanship – the mark of a diplomat or an artist. Jan was both. We all liked him and could work with him because he was a genuine humanist, open to all manner of book binding, from contemporary books as fine art, to the most anal

demands of historical conservation. And he was also perfectly happy to rebind family bibles and yearbooks. He just plain, out and out, was not a snob. It was all good.

Still, historic books have a look and odor about them. Heft a renaissance tome and you have substance in your hand. It’s been handled by all manner of saints and sinners – smells of where it’s been. And Jan Sobota was truly a renaissance man – one so renaissance that he’d know his way around a Gutenberg Bible or fearlessly cut into far older parchments from the hands of anonymous monks in medieval scriptoria. For Jan, the 14th century was just yesterday. Historical events and personages of the middle ages? As familiar to him, as the terrain in his own garden. The people back then? No different from any of us. Will it be Cholera or AIDS that kills us? Perhaps it will be Mongol hordes or Russian tanks. Going in for an appointment with the Gestapo or Communist Party worker cadres can’t be too different from answering questions at the offices of the Holy Inquisition. And insider trading? Kickbacks? Fraud? Treason? Fratricide? What’s new in any of it? The actors change roles and the show goes on, from one century to the next.

There’s nothing quite like seventeenth century Bohemia, the dead center of Europe, for particularly thorough violence – with the Bubonic Plague stepping in afterwards as mop-up crew. Near the ancient silver-mining town of Kutná Hora, at a bump in the road called Sedlec, is an otherwise unremarkable country chapel, but for its ossuary decorated with the bones of nearly forty thousand people. Mass graves from the time of the black death in the 14th century and Hussite wars in the 15th provided the building materials, strung together as chains, garlands, sconces, coats of arms, alters and you name it. The sign at the entryway says: „That which you are; we too once were. That which we are; you too shall be.“ Unequivocal. The empty eye sockets of tens of thousands of human skulls mounded up in the cool half-light with chandeliers of human scapulae and sacra overhead have a way of equalizing all else in life – all the vanities of our oh-so-precious individuality. You look closer and there are femurs with sabre wounds that have healed over and skulls that are cloven by axes. Violent times.

The chapel at Sedlec was rebuilt after the major blood-letting of the thirty-years war as a memento mori – reminder of death. Bohemia lost 80% of its population in that short time-span. Their neighbors in Bavaria, Saxony, and Silesia didn’t fare much better. These are perspectives I learned to make my own, sharing books and beers with Jan – books that eased the transition from one century to another – glancing daliances with Holy Roman emperors, defenestrations and treachery – all recorded in aging volumes by steady hands familiar with ink, quill and vellum; by skillful people who cast type and set it themselves; who codified the standards of modern orthography over issues of casting and setting type; by thoughtful people who wrote lucid thoughts and who also knew their papers and bindery materials – our spiritual progenitors. It‘s good to know them so immediately – by their work. The real stuff, worth remembering, worth rereading and worthy of great binding. Colleagues are where and when we find them. I talk to Rembrandt in the studio, about composition, about line, about content – but then again, so is it with Spinoza. Other times it’s Comenius or a contemporary writer. It’s all housed in books. Their ideas live while we honor them by reading and making them our own.

As long as we’re at the Age of Enlightenment, why stop with the seventeenth century? I recall a film about the exploits of Baron Von Münchhausen (Baron Prášil in Czech – or the Baron of Tall Tales). It opens somewhere in Europe, during the age of reason and bombs are bursting over an elegant city. Human body parts are again flying and the Baron is at his best defeating Turks and evading friendly fire from buffoonish generals. Those monkey brains of ours just keep chattering away – synapses firing in overdrive, coming up with new and improved ways of making human body parts airborne as new generations of young men respond to the appeal of spiffy new uniforms and adventures in the killing fields of the world. And they, “ pile them high at Austerlitz and Waterloo” to let the grass do its work. It covers all. How barbaric, we say, to wage war on the basis of minor differences in religious practices, when we’ve learned to defer the pleasures of such high adventure, until provoked by soaring gas prices or unsettled commodity futures markets.

What can you say about the mounds of dead, the ruined lives, destroyed nations and misery multiplied by millions that isn’t trite or self-evident? There are those who write War and Peace, but for most of us, it is the understatement that still allows us to get up in the morning and go to work - a little irony or hangman’s humor here and some whimsy or diabolical satire there and we’re good to go. Look at Jan’s bindings and on the surface it’s all ships of fools and hanky-panky but peel back the first few layers of the onion and you’ll see that beneath, it’s all informed by the inquisition, plague and war – as well as by Jaroslav Hašek’s, Good Soldier Schweik.

But then I pan over to other fields – not the kind where the grass is composting my fellow man, but to fields of endeavor where the ferment is of ideas recombining into ever more refined ways of thinking. The activity isn’t as loud or immediately compelling as violent death multiplied by lots of zeros, but it is real. Like Jan, I bear witness to the work of that less brutish side of who we are. My people are the people of art – people of the book. We are a counter-weight whose work fills libraries rather than airwaves. Our kind makes your art, writes your music and publishes the books that record it all. Kill and be killed if you must, but if there is to be a legacy of your brief days here, it will be our kind who witnesses it and forms the letters into the words with which it is described for posterity. Stalin could kill people, but Mandelstam and Solzhenitsyn recorded it. Powerful juju – and that too is reality.

Jan knew history. He was comfortable in his tall, narrow house in Loket, with its walls built to withstand Avar incursions and marauding Tatars; comfortable peeling back layers of 17th century paint to reveal 13the century frescos. He just made his books and nodded to the passing apparitions – minding his business. When the dust does some day settle, books he bound will still be here – elegant and serving a need. The politics and schemes of the moment? Yesterday’s news. And yesterday’s news? Good for wrapping fish. Ars longa. Vita brevis.

I once lived at the Golem house in Prague – at Meislova ulice, number 8, in the old Jewish ghetto. Appropriately enough, I shared those digs with astrologer Ada Svobodová. She knew the dissidents around town, and so early in 1990, when the government was in precipitous transition, she taught me some of her craft and together, we worked late nights up there in the Golem house, studying the natal charts of potential appointments to posts within the new government, ascertaining who might be fit for public service and who would probably fall short.

Horoscopes might seem a curious basis on which to select ministers and diplomats, but it is also more common than you’d think. If nobody from the old government is trustworthy and you are new to the racket, how do you choose functionaries and advisors? High school chums? Drinking buddies? Money under the table? In the fall of 1989, Ada told Václav Havel that he would soon become the leader of a revived Czech nation, and to be careful in the near-term. Death by drowning was indicated. He pooh-poohed the superstitious woman and proceeded to get roaring drunk with his buddies. Late that night, when crossing a field to get back home, he stumbled into an uncovered sewage pit where an outhouse had once stood and nearly drowned in human excrement. The bedraggled, nauseous, reeking, gasping, sputtering and chastened Havel, became a believer and astrology entered the arsenal of his tools of statecraft.

Picture the scene before you: It’s a late night in Prague, before the Marlboro man dominated every street corner, even before the neon of casinos and the vulgarity of Golden Arches assaulted the nightwalkers’ eyes at all hours – back when darkness, oh yes, that beautiful comforting velvety, all-enveloping and blessed dark, broken only by the moon, stars and late night taxis, still ruled the streets after the sun went down. Picture all that with an organic hodge-podge of gothic spires casting deep liquid shadows and you’ll be there with us – Prague astrologers in some century or another, quietly working out aspects of the progressed natal charts of potential aspirants for ministries with portfolios. A quiet city that knows how to keep its secrets and somewhere up on the fourth floor in Meislova ulice, a doorknob deliberately turns. The door opens and closes – not fast – not slow. The knob returns again to its original position, as the door is closed and the lock clicks back into place. No person to be seen, but a cold breeze passes through the room. We say hello to Golem and go back to our calculations.

The Golem was a mythic being of Jewish folklore, created from clay and quickened by the Shem, a magical stone engraved with an ancient Hebraic inscription, inserted into Golem’s forehead. The Golem of Prague was the best known of several golems and was created by the great mystic rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel in the sixteenth century. It is said to have gone rogue, causing great damage before being stopped by its creator. It is also said to be in storage somewhere in the old ghetto. Hitler’s minions spent quite some time looking for it, but came up empty-handed. Prague (or Praha) is a city filled with that kind of lore. Emperor Rudolf, Paracelsus, St. Germaine, John Dee, Fulcanelli, and Edward Kelly – they all pass through Praha – threshold of Europe. It’s there in the etymology of the name itself. Prah. It means threshold in Czech. I took my turn in the city of alchemists and astrologers and I too, crossed that threshold. Enriched by my days of being nurtured by Prague, Matkou Měst (Mother of Cities), I moved on to meet my destiny with art. If I hadn’t been suckled by Prague, hadn’t learned to love her ancient ways and dark stonework, there’d have been no pathway to Jan Sobota – no life in the book arts for me.

Jan and I shared a love for beautiful Czech books. This is something that needs to be elaborated for the non-Czech reader. Small nations feel threatened by the sea of others who do not share their love for that rarified language, spoken in the few watersheds that constitute a small country. Think about it; indigenous cultures are typically just a major watershed or two. There’s the heartland – typically a fertile plain that generates population and wealth. Then you go up the valleys, past mid-sized towns, villages and farmsteads, then into forests and up to the mountain crests and over to the other side – where another language has evolved in relative isolation. That language belongs to people with whom your people rarely crossed paths, but for a little smuggling of contraband, an occasional stolen bride and sporadic border skirmishes.

The maternal tongues of these small nations have miraculously survived all the invasions, floods, plagues and foreign occupiers to this day – a gift preserved and delivered to them across the generations. And the large nations aren’t really nations at all, but political assemblages – each a patchwork of small nations who were absorbed by their conquerors into heterogeneous empires. The relationship to a new language among colonized peoples may be very full, as is that of the Irish, Americans and Hindus to the English language, but it is no longer laden with the emotional charge of responsibility to maintain it as an ancestral heritage. English is flexible, useful and interesting – even beautiful, but it will do just fine with or without any of us.

Minority languages, on the other hand, carry an emotional load that can scarcely be exaggerated. The inheritors are understandably loath to just relinquish them for the convenience of larger political unions and international tax collections or to accommodate labeling efficiencies of trade goods. National awakenings weren’t cheap or easy. Our ancestors fought hard to bring these national tongues, like Czech back from the brink of extinction. They represent a sacred trust, but also a burden whose weight can be considerable.

Language and culture seem self evident – just there, like water to a fish. You get up and have breakfast; you void your bowels; you breath and you talk. Where’s the big burden and having to save anything? When there is no foreign military machine rattling weaponry at the border or a logging cartel chewing up your home – no problem at all. The trouble is that there is an attitude abroad that, not only are truth and God one, omnipresent, omnipotent and indivisible; but that everybody must be the same, speak the same, spend the same money, worship from the same translation of the same text and mean the same thing by the phrasing of the words and what they are silently thinking about it. Without the external pressures of empire builders, social institutions arise naturally from a folk culture, as it generates a normal percentage of the exceptional and

gifted. But the weight gets progressively heavier for smaller nations, when the gifted are co-opted, hijacked or killed, and each remaining person has a larger portion of the embattled culture to carry. Imagine being a member of a tribe of 500 in New Guinea with a monstrous vocabulary and being one of several individuals responsible for remembering the names of rare plants and animals only seen every decade or two. Imagine being Ishi, the last Yahi Indian, who died in 1916 under observation by scientists in a San Francisco museum – like a bug under a microscope.

Ishi and his sister were the last of the Yahi tribe to survive the genocidal colonization of California. For about 40 years after the last great massacre of their people, Ishi’s family group dwindled away while hiding out in the thick undergrowth along watercourses below the slopes of Mount Lassen. They carried on a more or less traditional pre-contact Yahi way of life while moving around frequently and concealing their camps. Farmers would occasionally find their possessions and take them as souvenirs, unaware that the last Indians still lived in their midst. There were rumors of Indians in the bush, but they were generally discounted as the foolish fabrications of dreamers. It was 1911. Modern times. A wild Indian in California seemed unthinkable – like believing in the boogeyman.

When his sister died, Ishi could no longer share what was in his soul. For three more years he dwelled in silence, hiding out like a hunted animal. Survival had lost its purpose, until one day he gave it all up and just walked out of the bush, onto a road and into town to meet his fate at the hands of those who’d been mercilessly hunting down his kind. America had, however, changed and he was not turned over to a lynch mob. The sheriff kept him in a jail cell for safekeeping and called up the anthropologists at the Hearst Museum in San Francisco. The director was an intelligent German academic and highly sympathetic to Ishi’s plight. Dr. Kroeber befriended Ishi and truly did his best to help and to preserve what he could learn from him, but it was too late. The Yahi way of life was completely disrupted. Ishi’s people were dead. His homeland was lost. He shared what he could with the decent people at the museum, but he also died within five years – diagnosed with tuberculosis but of course, he died of heartbreak. It happens frequently throughout the world today – for logging concessions or for mineral rights, for trade, for convenience, for converts and chits leading to salvation, for all manner of imperial, administrative and business reasons. Languages are lost as the burden on their last carriers becomes too heavy to bear. Unlike the many other languages dying out in this time of mass extinctions, the history of Ishi’s last days is well-documented, a complete language and culture – one which he carried as a scar in his heart before he took it to the grave with him. That complex is extensively recorded and available in the museum. It is also dead.

Those whose language and culture are not threatened can never know the burden under which the carriers of small minority languages labor – nor how those in exile bring up their children to preserve that which is beyond their capacities to save. And they, in a desperate act of self-preservation, tend to run from the obligation, but with a sense of having betrayed something they can never recover – never make right. It is a life-long wound, festering with regrets and self-doubt, but a wound, which is unavoidable and only rarely healed.

But we are eulogizing Jan Sobota, you say to yourself - the book guy. What has this got to do with extinct languages of long gone Indians? And Czech is a language with at least ten million speakers – with universities and libraries supported by an army, with a banking sector and complete industries? And besides, who hasn’t experienced loss and pain? Give it a break, you think to yourself, and get on with life. You’d be right of course, but this is a piece of the makeup of Jan Sobota. If you are to understand the fat and jolly, generous fellow who was so expansive and kind to everybody, you’ll need to recall that secondary glint in his eye, the one deep in there behind the self-evident one, the place where profound sadness also dwelled. Recall the kindly tailor you’ve seen when he hands you back your clothing at a humble shop – the stooped old gentleman who would never say an unkind word to anybody, but whose forearm bears a tattooed number. Within that being lies a past that will remain a closed book, at whose contents you can only guess. Well, that too is part of the equation, for Jan had seen a lot and didn’t go into exile easily. He was well aware, that his own culture had been teetering on the brink of extinction several times in the last four centuries – even during his lifetime. They could well have ended up like the nearby Lusatian, Silesian or Polab nations, absorbed within a greater Germany in a European version of manifest destiny - the Drang nach Osten, or push to the east.

Jan was all about preserving traditions and the kind of ancestral knowledge that today is mostly enshrined in books. There aren’t so many of us who do that and the days go by quickly in which you do so little of that for which you were born. Jan and I were Ishi and the books we made were acts of defiance – an activity going against the current - away from the industrial uniformity of the modern world, the one that is chewing up cultures and forests, exterminating the frogs and birds and by extension, all the many people who also need the forest’s protective canopy - us. You and me.

Today, the stories of our tribes are less and less passed on as oral tradition and most often read to us from the children’s books we’ve learned to treasure – illustrated by fine artists and produced with care for the highly discriminating purchasers of children’s books – for grandparents. Ask a children’s book author. It is indeed grandparents who buy these books. But all too soon, these gifts that have formed us from the very cradle, will be all we have left to remind us of their love – of the light in their eyes and the hope in their hearts, when they gazed upon us.

You don't casually toss such treasures into a dumpster. These are meaningful books. We spare no expense to have them rebound – like the family bible, where names and dates of ancestors are recorded for posterity. Damn the cost; it’s who we are and the last material vestiges of soulful encounters with our elders – one’s whose stories are slipping inexorably away, thinned by each passing year and generation. A treasure for anybody, but these kinds of gifts hold an even more exalted place in the hearts of small nations. Spotting them at a garage sale is all the more poignant, when the language is strange and nobody left who wants the old stuff – stuff that was made with love and self-sacrifice, but whose meaning is being lost for lack of a reader.

“Čertův Kámen” or “Devil’s Rock” was of the category of literature here being discussed. The tales therein recorded reflected the accreted wisdom and wit of a people as they retold them across the highlands in modest log cottages after the harvest was in. Among the interesting aspects of folktales is their fidelity to an original storyline, with only modest embellishments made by their tellers to accommodate the times. Ethnographers find that folktales from Bohemia and Bavaria have many of the same basic structures as those from Celtic bastions in the British Isles, even though Celts as a distinct culture, disappeared from central Europe sixteen hundred years ago. It’s a remarkable level of continuity.

Grandfather owned a sawmill and traveled about the highlands in search of lumber. Occasionally he’d tarry after contracts were signed to share a snort of Slivovice and hear some stories. He was one of few with a car in the 1920’s, so from time to time he’d give the elders a ride and usually hear a few more stories. He recognized the value of what he was hearing – knew it was the tail end of the vernacular culture and took the time to write it down. It was the real stuff and right as rain.

Jan Sobota also saw the value in these tales about the Devil in the highlands. Even more intriguing; they were being produced by the writer’s grandson in America; not so far from Cleveland. He was printing them laboriously by hand when, for political reasons, they couldn’t be published in Czechoslovakia. The writer was a businessman, a landowner, a kulak and an “enemy of the people”. He had to be suppressed and his children hounded out of the country, lest they write down some folk stories – hounded out like Jan, lest he too do something similar. The mirror was there, held up to his face. This concatenation of unlikely events was too good to be true, but following up on such leads was also emblematic of who Jan was – the way he chose to spend the allotted days he had for walking this earth.

Jan and I were both molded from an early age by children’s books and stamps designed by the likes of Max Švabinský, Alfons Mucha, Josef Lada and Mikuláš Aleš. When a new Czech Republic arose again from the ashes, they selected an artist to design the money – Oldřich Kulhánek. I can scarcely imagine bureaucrats in Brussels or Washington allowing a living artist anywhere close to their currency – but Hungary, Latvia or Macedonia – you bet. Small countries are where the usual market efficiencies must often fall before other, more pressing needs. On the other hand, they bring diversity to the human condition - a different way of seeing and being. And in diversity lies the salvation of every ecological system. We are not so different from a forest. Nature loves variety. God smiles upon imagination.

In 1986, I became friends with master printmaker Ladislav Čepelák. A professor at the Art Academy in Prague, he once taught etching and lithography to my wife, Jana Bártiková. My friendship with Čepelák also helped lead me to Jan Sobota and the book arts. His workshop in the corner tower of Mostecká and Malostranské Náměstí in Prague was what artist’s studios are supposed to be – insect collections, bird nests and dried flowers; cigar smoke and wine smells, all mingling with the vapors of etching inks and varnish from a clamped and drying Viola d’Amore. In the corner of the studio, stood a wooden etching press he’d once made. Modeled after the oldest presses, with simple wooden plain bearings and lubricated only by sheep tallow, it took an excellent impression. Here was an elder printmaker to emulate, one whose vision far transcended his own time. And he generously allowed me to enter this world he’d created.

Čepelák employed binders and typesetters to present complete suites of his work and in this too, he introduced me to a new world. The publishers of Czech bibliophilia were venerated heroes for me – Gods atop Olympus (or perhaps Říp, to stay with a Czech mystic mountain) and hardly approachable to mere mortals. Čepelák opened those doors for me. I peered through and eventually entered into collaborations with Vladimir Beneš at Bonaventura Press and Milan Frídl at Lyra Pragensis – with Jan Sobota’s participation at the bindery level. My etchings were printed in the workshop of a multi-generational family of printers named Dřímal, at an obscure back street Prague address called, “v Lesíčku“. That is too good to leave untranslated. The man‘s name means “Dreamer“ and he lives in, “the little woods“, but of course also in the shadow of the presidential castle and house of parliament. The family has dwelled within sight of the seats of power, pushing copper plates through a press and outlived the Hapsburg Monarchy, First Republic, Nazis and Communists. Salt of the earth doing the good work.

It is all handwork. It glows with the intensity of that which is undeniably real. It’s what Jan and I saw in each other - what we shared. But it isn’t universally appreciated. A friend in the US once picked up a book in my studio and off-handedly asked whose basement it had been made in. I was quietly offended, but with time, I realized that there is no shame in the many nicks, scrapes and imperfections; the drops of sweat and finger oils having been rubbed into the leather covers by being touched enough to have left a patina. The brand that appears in the leather of a binding that tells you it was once a cow on a ranch - they are all marks of honor.

Jan’s bindings weren’t, however, basement material. They were tight, but the slickness of a commercial product was not an aesthetic to which he aspired. Working with Jan I learned to love the individuality of well-crafted imperfection. There is a seeming contradiction to the excellent craftsman who could match a machine for quality, but who chooses to stay with the old ways and eschew the economies of scale. Obsolete technologies are often adopted by artists. Letterpress is an excellent example; wood engraving another. Jan’s books were like that – examples of perfection in the craft of binding and not there for daily use, but to keep alive what truly inspired book making at its highest level can be.

The book you hold isn’t one that Jan ever touched, but he was my model. The way of working belongs to the Sobota vision I addressed earlier – the honor and soul to be found in conscientiously made handcrafts. So allow me to walk you through those stages. The etchings here are not reproductions, “shot” from some original. They are printed from copper plates, which I created in the studio, as it has been done for the last five centuries. These plates have been inked and wiped by hand, employing methods that would’ve been familiar to Rembrandt. The process involves getting dirty and sweaty. I crank the plates through a press whose structure is little changed over the centuries. I turn a wheel much like that at the helm of an old sailing ship, with full control of the process because I know how much pressure is being exerted – not by checking a digital readout against an owner’s manual, but by the most direct of methods – by trusting my body’s innate intelligence – muscle and bone, informed by decades of experience.

The papers in this book too, are little affected by the advances of recent technology. Cotton and linen fibers, beaten to a pulp, are scooped up from a slurry, onto hand-held screens by skilled craftsmen. The wet sheets are couched onto felt blankets, pressed, sized and dried. Easy enough to say, but it takes mindful practice to do this well. The papers came from Zdeněk Král – salvaged after his death. Král’s shop in the village of Předklášteří was situated at the base of the 13th century convent church, Porta Coeli or Nebeská Brána (Heaven’s Gate), just outside the medieval market center of Tišnov. These precious papers survived flood and fire until the day I arrived. The intact packages were still there on their shelves, all duly graded, labeled and priced, awaiting an owner who was never to return. His widow allowed me to buy what I could carry.