Members of Little Traverse Band of the Odawa Nation explained to me the process by which the trees were marked in their own tradition. They’d cut the main-stem of a maple, just above the lowest branches, at a growth stage when the apical meristem would no longer regenerate. This resulted in trees missing the upper dominant trunk, but with strong side branches that resemble raised hands with open palms. Directed to many an ostensible location of these trees - at an auspicious crossroads, in front of a particular barn, within a certain Indian cemetery - I’ve discovered that they have mostly vanished, the inevitable casualties of groundskeepers who see an aging tree it as a hazard, rather than as a cultural landmark.

The era when our present culture swallowed up the indigenous cultures is a defining inflection point in American history – a fulcrum around which our common destiny still revolves like a merry-go-round of land titles, war, genealogy, birthrights, governance, mythologies and inheritance. Marker trees are a living link to that earlier time, before the long-reigning balance was tipped. They are icons and carry the trace of a biological memory accreted slowly with each year's ring of growth. They are real; you can touch them; they are alive; they are worthy subjects for art.

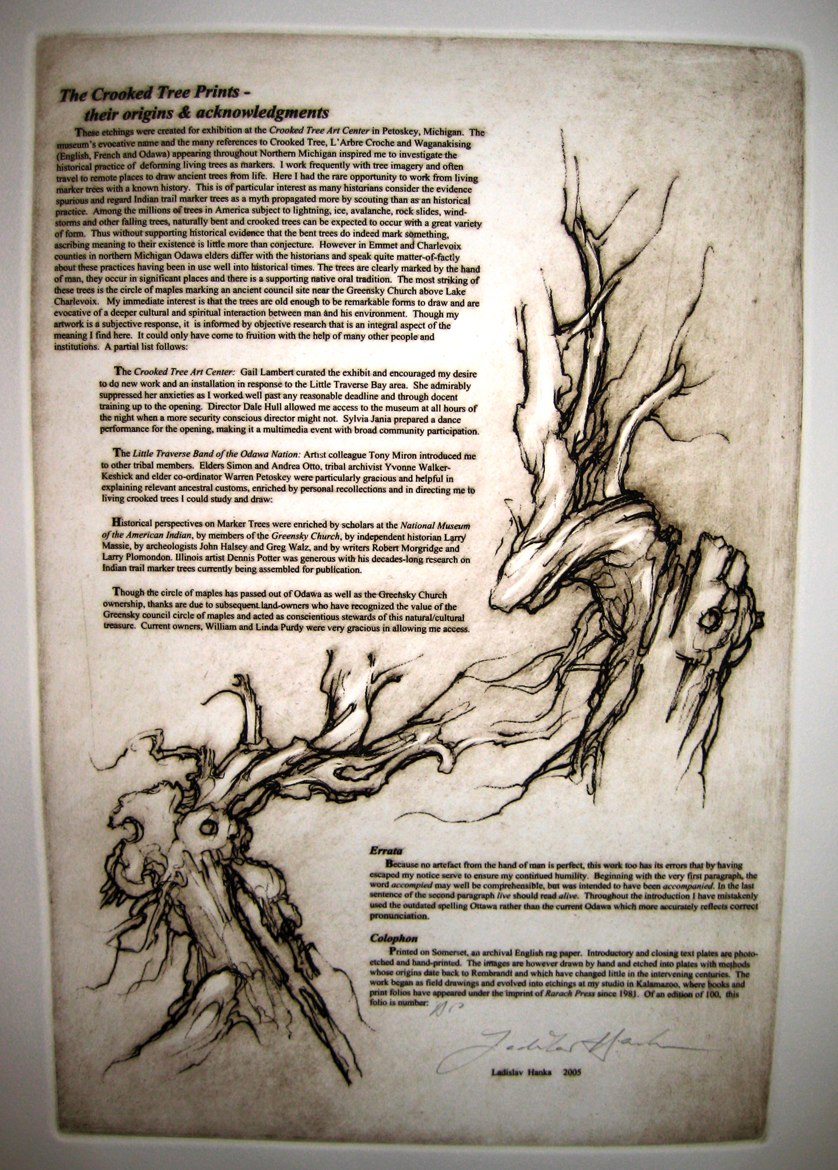

In these etchings I explore the Native American practice of marking significant places with trees that have been purposefully deformed to create living signposts. These marker trees were mostly along ancient trail-ways and because those native trails have become our modern-day roadways, few of these remarkable trees have survived. The handful I did find, have served as my models.

Many historians regard trail marker trees more as myth propagated by scouting than as a verifiable historic practice, yet I found Odawa elders willing to speak to me about these practices. Often times they still knew who had been maintaining the trails and who last marked the trees. The oral tradition is intact and to me that is evidence enough.

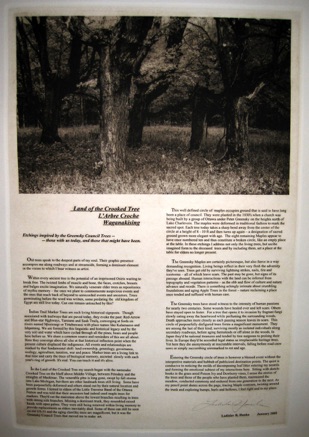

Of the several dozen marker trees I saw throughout Northern Michigan, it was the circle of maples planted near the Greensky Native American Church that moved me most. This well-defined circle of maples above Lake Charlevoix had been planted in the 1830's when a church was being built on a former council site under the leadership of Native American pastor, Peter Greensky. The Odawa culture was still dominant in the early 19th century, but their language and traditions were hybridizing with the new and finding a balance. The maples were planted to designate this new place of worship and though it was to be Christian, the congregation was still Odawa. They altered the trees in traditional fashion to honor this location that would continue to be sacred to their people.

opening and closing pages

Land of the Crooked Tree

individual prints (12 x 18 image): 350.00 each

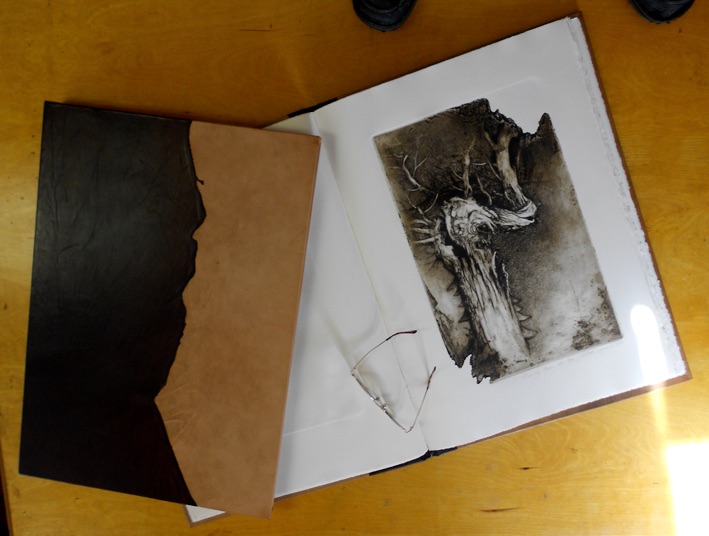

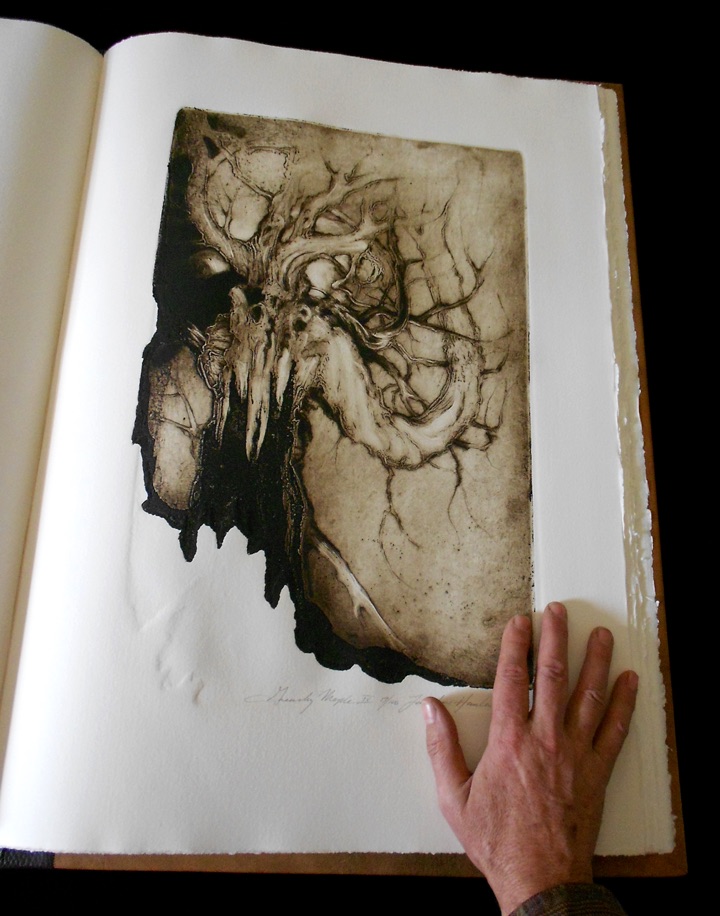

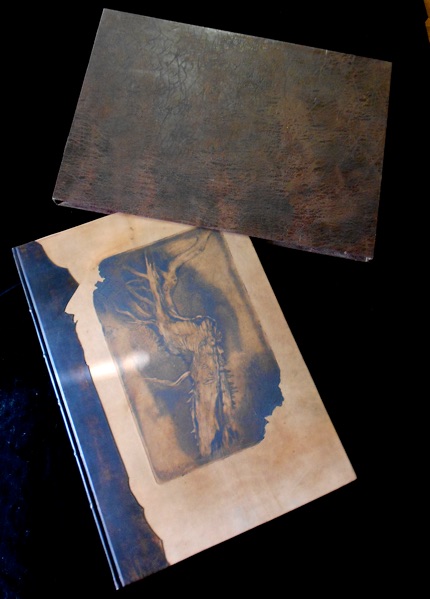

Unbound folio of 13 etchings

& two text pages: 4,500.00

Complete Book bound in full leather

with slip case: 6,000.00

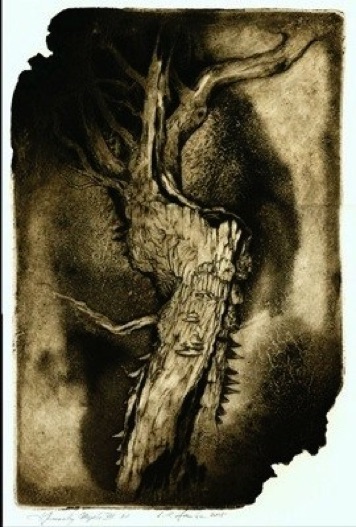

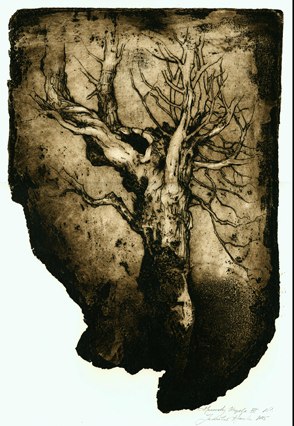

Greensky Maple VII

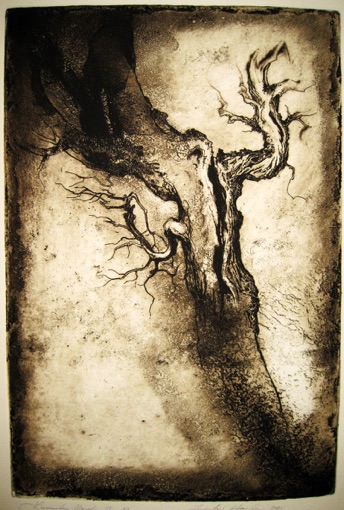

Greensky Maple IV

Greensky Maple V

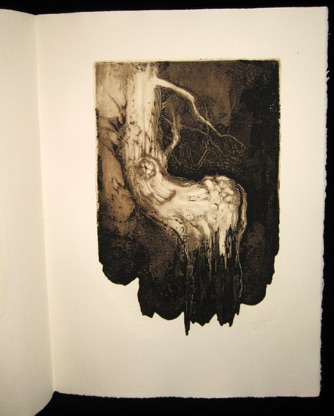

Greensky Maple VI

Land of the Crooked Tree as historical document

This is the most ambitious book I have produced. documenting a relatively unknown aspect of Native American history from Eastern Woodlands Indians traditions. This book is accompanied by a catalog which is printed bilingually in English and Pottawatomi, the indigenous language of southern Michigan. Potawatomi is a variant of the Anishnaabemowin language group – dominated by the larger Ojibway & Odawa tribes. The Pottawatomi traditionally inhabited a swath of southern Michigan and Ontario, across northern Indiana and north-central Illinois and southern Wisconsin. Many were removed to Oklahoma and Kansas where the bulk of their population resides today. It is exceedingly rare to see any native language appear bilingually in this way and thus few of us in the USA today, have ever seen written written or heard spoken the language indigenous to where we live. I never did until I had my own writing translated.

Each of these trees takes a sharp bend away from the center of the circle at a height of about three meters and then turns up again, a dramatic and elegant designation. The eight remaining maples appear to be missing one or more to form a symmetrical circle. One tree is said to have fallen in a windstorm in the 1950s and there is said to have once been another outer circle of nine more trees. The Greensky council trees today constitute a broken circle. In these etchings I address not only the living trees, but ascribe imagined form to the deceased trees. By including them I close the circle once again, and set a place at the table for the elders no longer present.

The remaining marker trees are fierce in a way that demands recognition – reflecting the adversity they have survived. The many random events that endanger living trees - the lightning strikes, road crews, nails, saws, fire and ice storms – all leave scars. All these etchings become portraits of noteworthy individuals who stand out as different than the evenly grown tree in the healthy vigor of youth. They are of course Maples and not Redwoods. Therefore the natural limits of their lifespans have about run out. The remaining survivors are isolated individuals along secondary roadways, guardians of aging farmsteads or Last Mohicans, off alone in the woods - disappearing anonymously, falling before road crew saws or simply succumbing, unrecorded, to rot. Their time on earth is running out.

Dwelling with these trees and drawing them was a prayerful activity. Turning these works into etchings in the studio took the activity beyond journalism, beyond the recording of passing historical events and personages and into something more ambiguously meaningful.

Ladislav R. Hanka

Land of the Crooked Tree

L´Arbre Croche

Waganakising

There are extremely few native speakers left who speak Potawatomi, much less being literate in the language and yet I found a Native American scholar to translate - and a young one to boot. Mike Zimmerman is fighting the tribal hierarchy in all the stupid ways that happens around casinos and who's people were important and who's ancestors meant nothing in the day and all that foolishness, but he is highly intelligent and due to break through someday and be recognized as a scholar and promoter of his severely endangered language and culture. Any help along the way that we can afford is effort well placed in the right direction.

But getting back to the artwork – those rare aging trees that the Indians have marked in the way I have here documented are at the age of senescence and death. I have marked a passage that will be unobservable in a few years. This is a part of my vision having to do with an aesthetic view of society and the way one lives with the land rather than in conflict. Indigenous spirituality, which grows from intimacy with the sun, rain, earth and the plants is not so different in the prairie landscapes inhabited by the Potawatomi from that of Central Europe, inhabited by my ancestors – and that too has similarities with the native wisdom of Tibet - all places I have come to know and love. It’s a relationship with the source of life that is concrete and not so abstract. Time spent observing and allowing the subtle voices to be heard has its rewards. When a tree speaks or a ghost appears, everything changes. The gifts are not distributed equally, but to those who open themselves up to them.

From among my many bookworks, the Land of the Crooked Tree stands out as having a certain kind of significance that is conducive to description. You can wrap words and concept around its structures. What makes this book a museum piece is that it's large and showy and demonstrates mastery of the medium of course, but also that it’s a complete package with documentation. It could not have been done by anybody else at any other place or time. There exists here a noteworthy confluence of events and personages that culminate in this work with a catalog that adds more to its appreciation. The double elephant folio format of the crooked trees is itself interpretive art and not mere photographic documentation, but these are also portraits of individual trees with character that the conditions of their lives have inscribed in their visages. The work marks an historical passage which will soon be unobservable. It all exists, almost with a sense of inevitability, but also with a sense of the unlikeliest concatenation of events leading up to it. I might not have developed an interest until all the trees were sick or cut down and simply never crossed paths with the one willing translator. There may be others, but I’ve looked for them before and turned up empty-handed. The trees too tend to fall before road crews widening the roadways and there are very few left. They are also mostly Maples and not Redwoods. Their natural life spans have about run their course.

As far as I can tell there really is next to nothing written on the practice of marking places, territorial boundaries and trails with purposefully deformed or Crooked Trees. I have looked and found only anecdotal scribbling and wishful thinking on the internet, but hardly purposeful scholarship or even levelheaded observations from amateur historians. There is a general level of awareness that such practices may be a part of Eastern Woodland Indian lore but there is little recorded. The only books I have found were more about trees than ethnography. The exception is Dennis Downes, whose book on Crooked Trees appeared about a year ago – an enthusiast of a lay historian, he has done his homework. Historians tend to question how much of the Crooked Tree lore is really legend and how much is more a matter of Boy Scout stories, but I have gone to the Native American elders and found that certain trees do have a local documentation surrounding them and that others simply have a solid oral tradition associated with them. The people who did this passed on the stories to those who still remember them. I may be minimally recorded, but it is real..