The Honeybee Scriptures

This is a copy of an article that appeared in Amsterdam Quarterly — issue 25. It is largely an adaptation of the introduction to a book I am preparing on the collaborations with Honeybees that I have been exploring for several years.

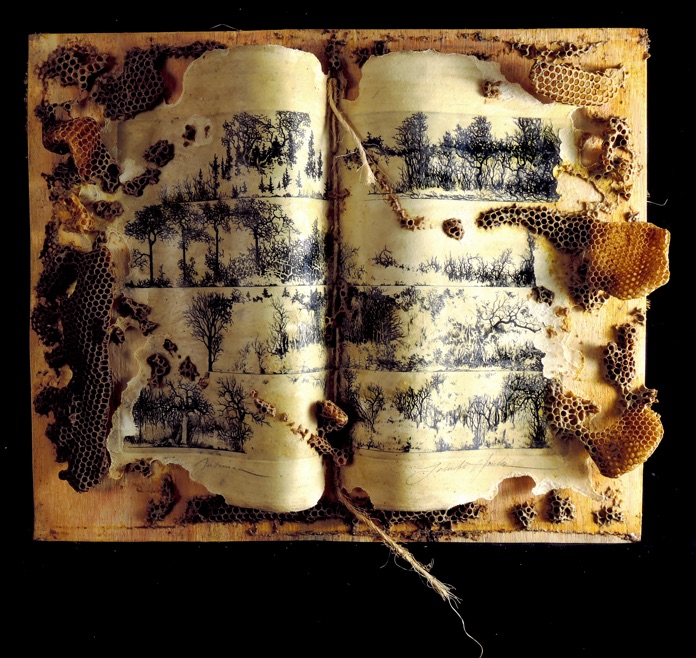

I am an artist and keeper of bees — two venerable vocations whose roots extend back to the Neolithic Age and into a time when the roles of artist and shaman were essentially interchangeable. The several etchings you see here, encrusted with amber-hued beeswax, are made in the time-honoured way, much as Rembrandt recorded the Dutch landscape on copper plates in the 17th century. They are made by hand and rely upon extensive fieldwork before being completed in studio. These works often take on a second life, when I insert them into a living beehive, where bees take over and continue the now collaborative creative process.

Bees will eventually cover everything in wax or even capped honey — or conversely, they may take a dislike to the intrusion, in which case swarms of little critics will start chewing up my precious artwork. I must therefore continually monitor the hive in order to reclaim my work when I deem it to be completed.

Entering the hive to check on developments is not as dramatic as you may think. Generally I can dip my hands into the living, swirling bug soup unmolested and inspect my art as well as the larval bees and honey stores, while the bees go calmly about their business. There are, however, days when bees soon become agitated and then the interspecies communication is direct. If you are willful enough to ignore guard bees bouncing off your forehead, you deserve to be stung – and yes, I do get stung.

Ladislav R. Hanka, Cottonwood Trinity Enfolded in Living Amber Honeybees, © 2017, etching with drypoint and beeswax added by honeybees in a living hive. Collection of Kalamazoo Nature Center, Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA

The scene is of an old woman, home alone and watching TV, when they announce a contest for the most beautiful tree in all the land. This gets her attention, for she has a grand old pear tree in the garden — her companion from childhood. Like herself, the tree is growing old and withering away, but clearly a contender. History and character are there in spades, etched into every knobby crook and knotted, gnarly joint. She takes a picture, sends it in and wins the contest. Happy as a clam, she hangs the prize up on the tree for all to see. A year goes by and they run the popular contest again, so she catches a ride into town for the award ceremonies.

The popular Czech comedian, Jaroslav Dušek, hosted that show and as he tells it, the previous year’s winner came up on stage and cryptically handed him a wine bottle. ‘Well now, dear Auntie,’ he asked her in his best stage voice, ‘what have we here?’ And she told him. without equivalent stagecraft, that her pear tree won the prize last year, and then soon after, began to noticeably green up, sprouting new leaves and even branches. But, that’s not all.

When spring arrived, her tree blossomed as never before and hosted absolutely remarkable numbers of bees. The ensuing fruit too, was bountiful and then received a full summer’s sun. Well, that dear old pear tree hadn’t born any fruit in years. As she watched those pears ripen to a full rich flavour, she knew she was witnessing a miracle.

And that bottle she handed off on stage? Well, that sweet little old lady had picked, mashed and fermented the pears herself and then carefully distilled the wine in the time-honoured way of her ancestors. She’d produced a powerful clear brandy — the very essence of all that is delectable about a pear at its late summer peak — and proof positive, that the dear old tree appreciated being noticed.

Still, the collaboration has been well worth any discomfort I may suffer. These wondrous, little beasties have rewarded my efforts richly, adding their accretions of wax in the exquisite ways with which Mother Nature has equipped them. I find their additions to be as inevitably elegant as the endless variety of gently curving veils of honeycomb you’ll find hanging from the domed ceilings within a bee tree. But why am I so taken with all this to stay with it for years? That is harder to say and requires reaching more for evocation and metaphor than relying upon direct answers. Perhaps a story is the best way to enter that unstable ground.

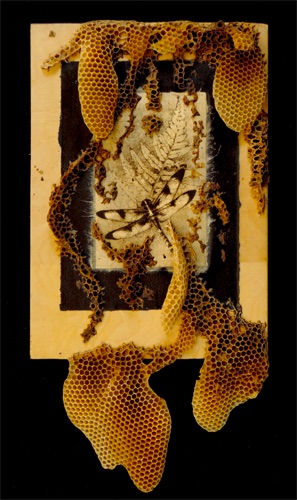

Ladislav R. Hanka, Dragonfly Embellished with Veils of Living Amber, etching with drypoint and beeswax added by honeybees in a living hive, © 2018.

Perhaps it is indeed the realization of a morphogenic field – of an artwork whose time has come and which desires to become manifest through the intelligence of the hive or perhaps all hives and all queens as one. Consciousness – perhaps it is indivisible — an omnipresent and universal attribute inhering in all material. Imagine that – and be consequential in your imaginings!

Other times the bees will begin to chew the paper away – get good purchase on an exposed edge and keep at it — all my efforts quickly going back to undifferentiated cellulose and tossed out with the dead. Then again, those remaining chewed edges can also be breathtakingly elegant as all nature ultimately is. Form and function. Evolution. Chance and necessity. Survival of the fittest – but not just the old red of tooth and claw saw, but also the elegant solution – like mathematical equations. It is so because it must be — cannot be otherwise. The destruction of a volcano or a flood is breathtaking even within its violence and destruction. The ruthless efficiency of large cats — a dragonfly darting out to catch a honeybee which it carefully holds away from its body as it delicately munches it down to the stinger and tosses it away — all much the same.

Night-flying Pollinators Embalmed by Honeybees, etching with drypoint and beeswax added by honeybees in a living hive, © 2018

My artwork extends to a fascination with bee trees — large, dominant trees with prominent features, in whose bark a mere fissure or knothole can lead to a complete world of domed chambers deep within, where legions of bees, guard their golden trove of honey. And then there are the parasites living inside the hive and pollination and the healing properties of honey and on and on it goes — one thing leading to the next — cycles without beginning, endpoint or resolution.

The beauty inhering in these works of art is, of course, based in the usual uses of line and composition to make some sort of elusive and nuanced statement, but beyond that is the synergistic effect that collaboration introduces to the process. We seem predisposed to being charmed by beautiful surprises more than by our own clever manipulations. I find that I typically approach the hive in anticipation of what the girls will have done this time – the smile that sneaks in unannounced when I open the hive.

What we are beholding here is nothing less than the elegance of form following function at the very level of biology, as the veils of honeycomb come down the fronts of my etchings and occlude some of my preciously composed works of art. Oftentimes those little pin-head sized brains of the cute fuzzy little bugs seem to comprehend composition and design and follow my lead as if they were colouring within the lines or picking up the motion I have begun and continuing with that rhythm in the media of wax, propolis and honey.

In both of these callings, as artist and as keeper of the bees, I am entering primordial, mysterious worlds that are at once alluring and potentially dangerous. But come walk with me to the studio and over to the bee yards. We’ll have a closer look. It’s no secret to beekeepers that our bees respond differently to our presence than to that of invading strangers. They know far more than you might think.

The brain of a bee is admittedly minuscule, but a hive can easily contain 50,000 inhabitants — which is equal to the population of a modest-sized town with schools, clinics, delinquents, police, sewage treatment plants and manufacturing. Bees clearly learn from experience and communicate within the hive what they have learned. But does that extend to actually being interested in me and my artwork? The additions they make do seem to have a compositional sense to them – framing devices of sorts – embellishments, but somehow appropriate. Bees appear to understand what the two-dimensional drawings and etchings I give them actually represent. I once even witnessed a queen respond to an engraved image of a bee several times her size – as if it were a living competitor. She tried to kill that depiction of a bee just as she would a strange queen trespassing in her hive — with a sting to the abdomen. To the biologist still dwelling deep within my bones, that sounds far-fetched, yet I cannot deny what I witnessed. Every bee-keeper has such stories to tell. Hunters, farmers and fishermen – much the same. Every dog owner knows their pet responds to them with intelligence and compassion. We are not so separable you, and I — we tool users and reflective beings — from the world we inhabit.

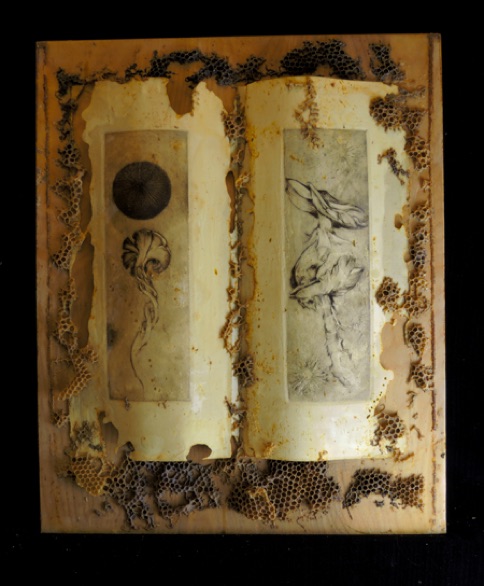

Ladislav R Hanka, The Book of Decomposers Ornamented by Honeybees, etching with drypoint and beeswax added by honeybees in a living hive, © 2017.

Ladislav R. Hanka, Fields Going Wild and Embalmed by Honeybees, etching with drypoint and beeswax added by honeybees in a living hive, © 2018. Collection of Midwest Museum of American Art, Elkhart, Indiana, USA.

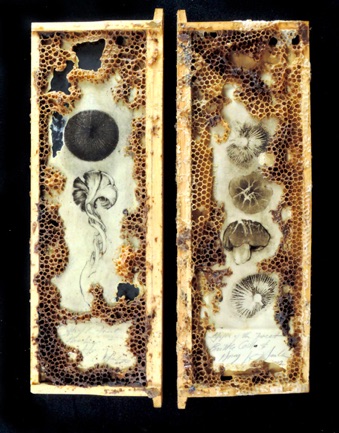

In the great cycle of being, creation and decomposition are but two sides of one coin recorded in this Librum aeternum on verso and recto sides of the same sheet. Bees pollinate and plants reconfigure the molecules of air, soil and water, which soil fungi then again pry loose from the dead and release back into the system. Of course, bees are in trouble and bee trees are increasingly rare. Crops are now threatened by a paucity of pollinators. Even the once resilient decomposing side of the cycle is weakened by pernicious pollutants, which, having no obvious chinks in their armour, are not easily broken down. All the earth is an interdependent system of connected vessels — much like the lava in one volcano, which recedes into the depths of the earth in response to the lava in another volcano hundreds of miles away swelling up into the cone and flowing up over the lip and down its fiery slopes.

Bees are my subject here as well as my collaborators and medium. Honeybees are, of course, in trouble and anybody who has not been living under a rock should be getting nervous about that and the source of their own food in the very near term. The artwork being immersed in hives is a culmination of thirty years of work as a printmaker and informed by my decades as a naturalist, zoologist, and environmentalist — even as a monitor of nuclear power plants and as a chemist synthesizing pesticides. I have at times worked for the evil empire, taken its money and eaten the food from its fields. Of course, when you get close to it, this evil empire becomes much more nuanced and composed of many disturbingly normal and limited people with complexes of mixed motives as well as needs and fiduciary responsibilities that lead to questionable choices made under the usual clouds of obscuring conflicted interests. How dreadfully ordinary.

Honeybees, however, are far from ordinary. They have not only entered my artwork, but gotten under my skin and into my blood. There is nothing quite like settling down in the grass after a day of tending bees, next to a hive and popping a beer. Going off into mid-summer reverie, I enter dreamtime as the workaday world recedes into mere background noise. The hum and the smell of a hive permeating my immediate environment is positively intoxicating, as bees alight on my skin, sniff around and fly off again — just doing what bees do. Such are the timeless, primordial pleasures that life can offer, when a stolen moment, shared with bees, telescopes into a glimpse of eternity.

And so I indulge in creating scripture, drawings and etchings — which are then annotated, redacted, and embellished by honeybees. I have also seen fit to tell my stories, not so much as definitive statements of truth, handed down from on-high, but in ways which I hope will open the doors of perception a crack and allow others entry, to observe the artist at play — as a fly on the studio wall. Storytelling has a way of going off on tangents that are indeed telling — that inadvertently allow something more to slip out. One’s nagging doubts and questionable motivations come out, alongside admissions of living with contradiction in an imperfect world — one in which we rarely live up to our own beliefs and standards. With some luck, even the big questions, so boldly sincere, we know not how they escaped our notice, will see the light of day — the ones that force us to look at the unexamined.

Opening a hive is good for clarifying the order of things — for getting out of one’s head and abstraction and back to the present — fully conscious. One’s attention assumes a crystalline clarity, when focused upon the sound of tens of thousands of buzzing insects, each with a venom-laden stinger just inches away. They get increasingly agitated as I reach in and pull out their winter stores. I read the ledger of their lives in frame after frame of brood and honey in order to manage the hive, but it’s not without its limits. There comes a point when they’ve had enough of my intrusions. They tend to let one know, but we do need to be attentive. Since I generally wear little more than light summer clothing, I really do need to be sensitive to their communication, or suffer the consequences.

Ladislav R. Hanka, Dragonfly Draped in Honeycomb,

etching with drypoint and beeswax added by honeybees in a living hive, © 2018.

Anna Ill Marovich, Lad with his girls, photograph, © 2017.

Well, my friends, I have drawn enough old trees, meditated in their shade and listened to them tell me their stories, that I know the truth about trees when I hear it. All the many creatures, with whom we share God’s green earth, wither away with neglect, or conversely, come to life and blossom when bathed in loving attention — me, thee, trees and bees included.

This is why I draw trees, mushrooms, minnows and spiders, and why I also talk to my bees. I urinate in the bee-yard to be sure they know my smell and they reward my attentions by working on my etchings with a sensitivity that speaks of knowing my intentions.

Bees do seem to know a lot and they clearly have a relationship with their keeper. Folklore is rich with anecdote about this. As recently as 2007, a Scottish newspaper commented upon an elderly beekeeper’s funeral near Edinburgh — that his bees swarmed and followed the hearse right into the churchyard. Attending their master’s funeral is a phenomenon that is often mentioned in the folklore of beekeeping. In my own maternal Czech tongue, there’s a separate word for death, when used for animals as opposed to people — except when bees die. Then we use the human expression for passing.

There is something special about bees and it goes way back — back before the word itself was even written. It may not sound like good science, but it is good myth, as well as truth writ large — the kind of truth with roots that run deep enough to sustain us in hard times. This is, of course, the very point of art — at least any art that hopes to feed our souls tomorrow, and next year as well. Such art must contain a generous spectrum of experience — from the mythic to the spiritual, the technical and serious, to the downright laughable.

There is an undeniable intelligence at work in a beehive. Working with bees you learn to respect that and indeed care about these endearing creatures and the folklore that has arisen around their tending and care. Esoteric traditions speak of an Akashic Record in which all things from all times are recorded and accessible to those who’ve earned the right of entry. Among the many works of art being harvested from my beehives, there are several fanciful entries into that very book of records, opened to pages featuring decomposers and pollinators. Elsewhere bugs and bushes will be seen intruding at the edges of untended fields, while under the surface, the roots of agricultural row crops are being infiltrated by beetles, snakes and Sassafras rhizomes. A book of books … perhaps a Scriptum Apium melliferum, or indeed the Honeybee Scriptures.

I’d like to do something about all of that, but I am neither scientist nor politician. I am an artist and a beekeeper — member of two ancient, esoteric brotherhoods whose roots reach back into the mists of time and down to the very bedrock of civilization — among the first professions. Seventeen thousand years ago, a colleague artist working in the Spanish Cave of the Spider clearly depicted a person collecting honey from a bee-tree. Our interactions with honeybees thus appear to rival those with dogs, pigeons and horses as the earliest domestication of animals. As conservators of ancestral knowledge, entrusted to be carriers of the culture, there is an added burden placed upon us to bear witness.

Ladislav R Hanka, Mushrooms Embalmed by Honeybees, etching with drypoint and beeswax added by honeybees in a living hive, Ladislav R. Hanka, © 2017.

Ladislav R. Hanka, Queen bee stinging the depiction of a much larger bee, photograph, © 2018.

Ultimately, we learn to care about that, to which we direct our attention. What is love, if not the capacity for inclusion and learning to care about that which is not just an extension of one’s ego? And art too, is typically directed outward to that which we behold of the world around – much more so than being a mere mirror, held up to our own precious, egoic delusions. What after all, does a Bach Sonata mean? Hard to say, but it seems to stay relevant over centuries, while the issues of the day change with vertiginous frequency. Music is a primary human concern, rather than something that has utility in the service of other ends. It has intrinsic value. We feel better for having meaningful music enter our lives, but it’s very hard to say how or why that should be. Good art works that way. And like rust, it never sleeps. AQ

Ladislav R. Hanka

The Honeybee Scriptures

Ladislav R. Hanka is an artist dwelling among the Great Lakes of North America. His artwork examines themes of life, death and regeneration – nature as the crucible in which man finds a reflection of his own life and meaning. Most recently this work has involved close collaboration with honeybees and placing his drawings and etchings into living beehives. This contribution to Amsterdam Quarterly is largely excerpted from a book currently being prepared for publication and entitled The Honeybee Scriptures.

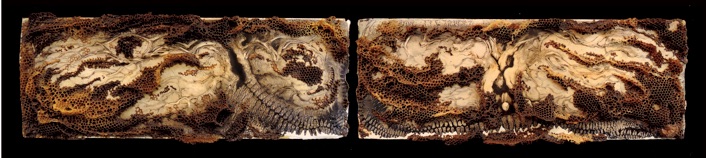

Ladislav R. Hanka, Tree of Life Meditation; etching with drypoint and beeswax added by honeybees in a living hive © 2018.

Collection of Gwen Frostic School of Art: Western Michigan University

Ladislav R. Hanka, Autumnal Fugue; etching with drypoint and beeswax added by honeybees in a living hive © 2018.

Collection of Gwen Frostic School of Art: Western Michigan University