John Voelker - Trout Madness

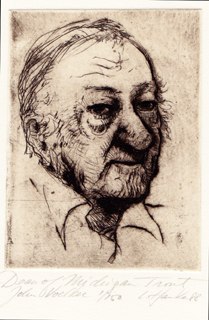

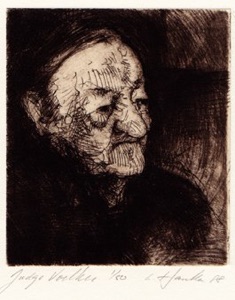

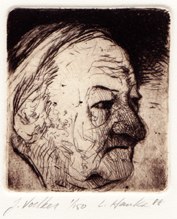

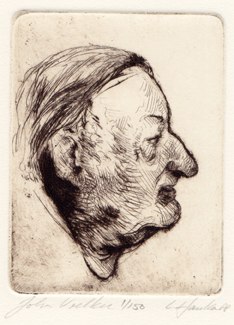

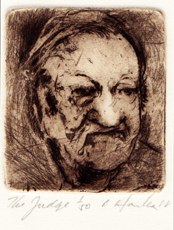

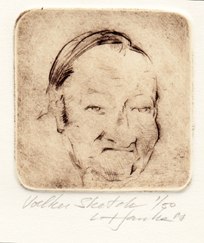

Potraits of the fishing writer John Voelker who wrote under the pen name of Robert Traver

Etching Plates

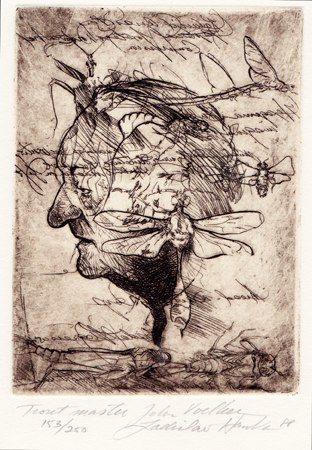

Trout master Voelker- 150.00

Dean of Michigan trout- 150.00

John Voelker Profile 100.00

John Voelker 3/4 75.00

The Judge 75.00

Aging Jurist 75.00

Judge Voelker 75.00

Voelker Sketch 75.00

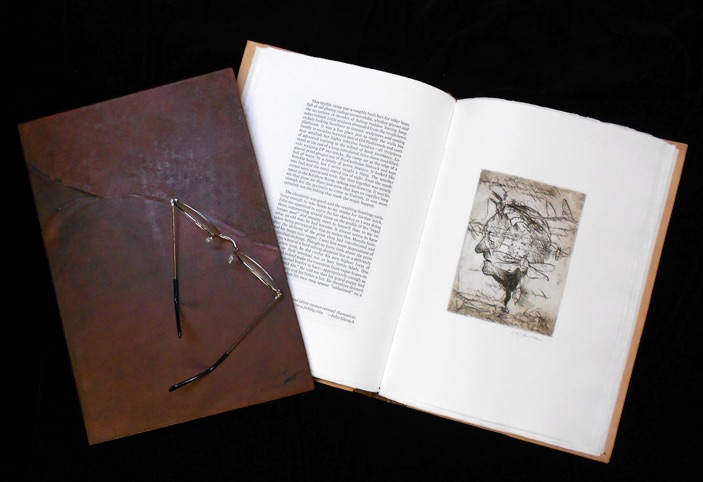

set of eight etchings with text set in letterpress 700.00

Set of 12 etchings and text in lidded &

hinged Cherry presentation box 1,500.00

Complete work with 12 etched plates and text

bound in full leathers by Master bookbinder

Vernon Wiering with leather slipcase 1,500.00

Dean of Michigan trout - 2 x3 inches

J. Voelker - 2 x 2 inches

John Voelker Profile 3 x 4 inches

Aging Jurist - 4 x 6 inches

Judge Voelker 3 x 4 inches

Voelker Sketch 2 x 2 inches

The Judge 2 x 2 inches

Troutmaster John Voelker - 4 x 6 inches

a print which certain gallery owners got in the

habit of referring to as - the “Bug-faced Voelker”.

The gods do not deduct from man's allotted

span the hours spent in fishing.

Babylonian Proverb

On the Genesis of the John Voelker Etchings

I first encountered John Voelker between the covers of Trout Madness (writing under the pen name of Robert Traver). This beautiful collection of fishing stories from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula appeared under the Christmas tree when I was eight – admittedly as my father’s present, but one which I quickly appropriated. Sensing the potency of the proffered vision, and desirous of making it my own, I snuck off with my new Christmas paint box and father’s book to plagiarize the leaping Brook Trout on its dust jacket. With the focused attention of a child, I copied the magical creature from the cover over and again, committing every spot, fin and vermiculation to the kind of long-term memory that will accompany me to my death bed. I read and reread the stories of the larger-than-life characters that peopled these stories – the moonshiners, poachers, game-wardens and small town justices of the peace. I took to the esoterica of fly-fishing as other boys did to baseball cards, easily imagining Royal Coachmen and hatches of Pink Ladies floating drag-free through swirling eddies of tea-colored water. I saw myself on beaver dams, making long and looping, but accurate casts to monstrous Brook Trout lazily rising from under cedar snags shaded by thickets of Tag-Alder and clouds of black flies. Northern rivers became the mythic places of my imagination, fully inhabited with the mysteries missing in my own sanitized suburban childhood.

I later learned to fly-fish and to tie my own flies, even selling them to my father’s fishing buddies when other boys were pumping gas for pocket money. After college I spent a summer living the Nick Adams stories on Horton Creek, a mile’s walk from the Hemingway summer house on Lake Charlevoix. The hunting camp I inhabited was said to have been built on the grave site of Ernest’s common law Indian wife and whatever the truth of the story, it felt like sacred ground and a gift to be there. I spent those days exploring the cedar swamps and beaver ponds of Horton Creek with fly rod and sketch-pad – becoming a connoisseur of the sights, smells and sounds that attend the pursuit of trout. At night I read and communed with the spirits of the place by campfire, absorbing what the dream-time held for me there. By summer’s end I’d received the vision of myself as both artist and naturalist – one for whom fishing was to be an important part of the greater mystery to which my life would be dedicated.

Like Hemingway and Nick Adams, John Voelker too was a part of the vision I’d received among the mosquitos and skunk cabbages of Horton Creek. His writing had fed my soul at a formative time and several years later I began to feel a need to honor that. Though it seemed presumptuous of me to intrude on the aging master’s privacy, I still wanted to meet him face to face – to make the trip to Frenchman’s pond and do some sketches. I began to make inquiries among fishing buddies who’d met him and they directed me to Pauly’s Rainbow Room, a modest tavern in Ishpeming. There, the master story-teller and former jurist could, with luck, be overheard making provocatively dismissive pronouncements about bait fishermen and perhaps be induced to have a drink or go fishing. I knew then that I had to make the pilgrimage without further delay.

In late summer of 1987 I went on a fishing trip, by way of Ishpeming. I stopped at the Rainbow Room and found that it was indeed hidden by an unremarkable storefront, there for those who already knew about it. There appeared to be little evidence of interest in attracting new customers - no open/closed sign, no posted hours – just a tiny name-plate in the window. Pauly, the bartender, was there alone that morning and tidying up from the night before. He was predictably non-committal in reply to my inquiries about John. His establishment was plain but comfortable, with a single lit-up beer sign and welcomingly worn wooden booths. I spent an hour drawing Pauly while nursing a cup of acidic bar coffee before John came in for his morning coke and cribbage. From the exchanged glances between the two, I appeared to have been provisionally approved by the guardian of the threshold, probably for not having chattered needlessly.

I’ve done a lot of anonymous drawing in public places and am good at surreptitiously snatching a likeness and slipping away unnoticed. There is however, nothing anonymous or even subtle about two people in a well-lit bar, the one sneaking glances at the other while sketching. Never the less, I began sketching from my table across the room and when he addressed me, I simply asked John if it were all right. He was amused by the prospect of being worthy of documentation by the youngster in his bar (I was 35) and was fortunately in no mood to dissuade or escape me. I was invited to join him.

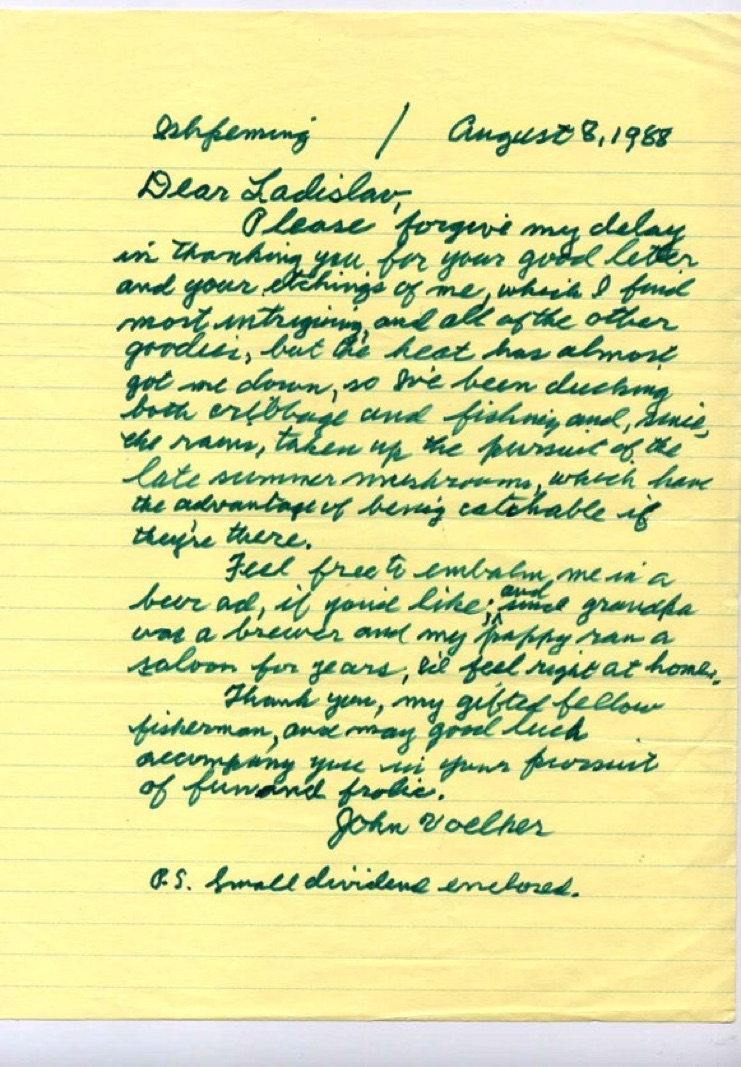

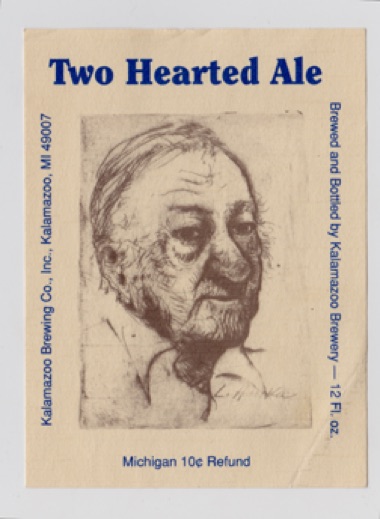

He did ask if I were planning to sell these drawings – a landmine of a question for the insecure younger artist. Groping in desperation for the right answer, I settled on truth and told him I’d sell virtually anything to stay in the studio and off the job-market, but that my prime motivator was no more pecuniary than was his own. I even told him that I’d been designing labels for a micro-brewery in Kalamazoo and that I was hoping to use his portrait for that purpose. When he saw that I was indeed realistically mercenary about my vocation and nobody’s fool, I appeared to have gained acceptance, perhaps even respect.

John and I fortunately spoke the same language. We’d both been stiffed by the same sporting journal and had each settled for life-time subscriptions to a magazine neither of us actually read. We were both opinionated cranks as well. I suspect however, that it was the prospect of joining the august company of the crusty alcoholics I’d been portraying for stout bottles or perhaps even becoming a Two-Hearted Ale icon that were the inducements to put up with me rather than my brilliant pronouncements on things he’d doubtless heard before. During the course of two mornings in the Rainbow Room he disparaged military bases, logging, mining and other mainstays of the local economy and I murmured agreement while drawing. We traded observations on the qualities of various mushroom species and laughed over the many pathologies of modern trout fishing we’d seen walking out of sporting-goods stores – mostly very serious types with too much money and way too much stuff – to be avoided at stream-side and bar-side as well. When I later pulled out copper plates and a diamond stylus, the portraits took on a technical aspect that further established my authority and by then, I had him. The hook was set solidly into bone and I was invited to retire with him for the afternoon to his fishing camp at Frenchman’s Pond.

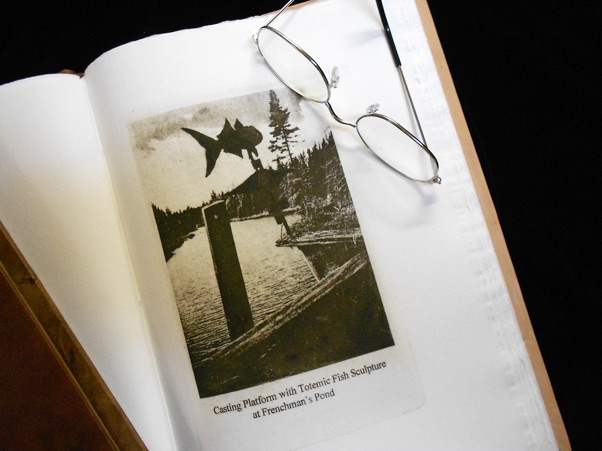

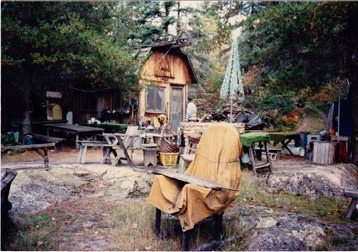

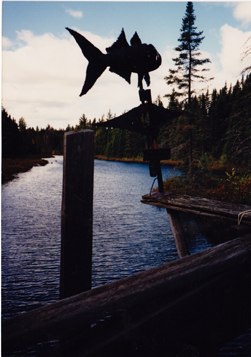

This mythic camp was a roughly built fort for older boys, full of old photos, college memorabilia, whiskey glasses and the accretions of decades of fishing buddies leaving keepsakes behind. Little projects abounded from the rough-hewn rickety-looking furniture to totemic sculptures and casting platforms. It was a fun place just to study the walls but mostly to socialize between sips of Old Fashioneds and casts over smallish but highly selective Brookies – all recipients of advanced training in the school of hook avoidance. Located at the end of a long convoluted drive down mud-filled, axle scraping UP two-tracks, the camp sat at the edge of a glacial pond gouged out of Pre-Cambrian bedrock and kept full of water by a family of active beavers. It looked like Brookie heaven, but I never caught a thing. The weather was foul and the trout stayed out of sight. Even the mushrooms were sparse and toxic. Our time together was mostly spent in the Rainbow Room, talking and drawing. It was his art that drew me there and mine that kept us together long enough for the portraits to come to fruition. It was most certainly not the fishing that made the magic happen.

The chemistry was good and the resulting drawings satisfying enough to take home to my studio for further work. John too appeared to enjoy the bar sketches as I was doing them, commenting several times on the profile of his “regal roman nose” and musing more to himself than to me on what an old man he had become. It almost seems to have taken being portrayed for him to realize this. Months later, after the alchemy of the print shop had transformed and fixed his image into copper, I sent him some impressions of the finished etchings. Though he knew little about the print collector’s love of a bold velvety drypoint line or a delicately wiped plate tone, he did confer his own highest form of blessing on their eventual use as beer bottle labels. One etching did indeed make the transition from vague hopes on my part, to actual bottles in bars – appropriately enough as a “Two-Hearted Ale”. He told me that his grandpappy had owned a brewery and his father a bar. He therefore deemed it only proper that his own mug appear “embalmed” on a beer bottle

Creeps and idiots cannot conceal themselves for long on a fishing trip. John Gierach

Adendum/errata

Some go to church and think about fishing. Others go fishing and think about God. Tony Blake

On the controversy surrounding these etchings

Because nothing involving art is simple or without it’s shadow aspect, I will acknowledge that even these small etchings depicting the grand old master of trout-fishing stories, done by a youthful admirer, are not without their human psycho-drama. The beer bottle label appeared some time after John’s death. Called Two-hearted Ale, it was intended to elicit Hemingway and the best of fishing in the fabled UP. The beer itself was a hearty brew - hops driven and yeasty, unpasteurized stuff with a sediment-load at the bottom of each bottle that is not a drink for the kind of whooses who follow hatchery trucks around to drain pipes on opening day to kill their limit of undersized pasty-looking mealy-fleshed fish, fattened up on Purina Trout Chow. No siree, this was the kind of beer a real man drinks - one who wades into swamps and pays with blood to fish over crafty, elusive and above all - wild trout. John Voelker’s portrait on one side and the familiar testament of a fisherman, on the other – these were the guarantees of authenticity. The bottles are probably quite the collector’s item by now, due to their short lifespan on store shelves. The label was pulled almost immediately after complaints from the deceased writer’s clan and legal team arrived at the brewery office. There were copyright infringements on the testament to be sure, but more importantly, there appeared to be posthumous desires to resurrect the image of their beloved grand pappy and husband that were fueling the protest from places deeper within the offended family psyche. The portrait on the bottle admittedly had a certain classic Rembrandtesque feel about it – but resembled his etchings of drunks, rag-pickers and plague-era rat killers more than it did his depictions of the fair-minded barristers of Amsterdam posing in ruffled collars before their tastefully appointed libraries.

I felt for the widow and aunts wanting to remake the image of the old man with a bulbous nose and ruptured subcutaneous capillaries in his cheeks – the interest drawn on years of investments made in Tennessee Bourbon futures. They wanted to turn that shameful picture of a fishing sot into a more pleasant and domesticated image of a proper pater familias – a fine upstanding member of the Rotary Club, graciously accepting prestigious literary awards in well-tailored suits. The trouble with that sympathy vote is that it conflicts with much stronger desires bubbling up from far deeper springs within my artist’s soul - and those desires (which really boil down to needs) - they push me to honor a colleague artist and fisherman whose memory I cherish enough to be truthful.

John Voelker struck me as more of an introspective and highly literate W.C Fields – a man who knows he has to make accommodation with the system and the female of the species, pay the bills, send the kids to school and not offend the church-going folks on Sunday morning, as he loads up his fishing gear. But he was also a man who’d escaped a lifetime sentence to the Supreme Court and who wasn’t about to lose his preciously won freedom again. I can easily substitute Voelker for Fields in the opening scenes of The Bank Dick - stopped short while sneaking down the stairs by a shrill voice from the kitchen - demanding to know if he’s been smoking again. The apprehended miscreant, skillfully flips the cigarette on his lip up into his mouth, folded into his tongue and facing into his throat, and with smoke rolling out of his eyes and ears, he mumbles a submissive “no dear”, and keeps sidling on past and out the door. At the bar he asks Shemp Howard, the bartender, if he spent twenty dollars there last night and when he is told, “yes sir, you did”, such a look of relief comes across his face as he says; “Thank God. I was afraid I had lost that twenty!” It’s a hopeless task to remake the public persona of somebody into a sanitized version to suit your needs. John Voelker needs no posthumous rehabilitation. He was a fine man with very human shortcomings. We should all do so well.

I particularly enjoyed John’s clear-eyed observations of his own foibles and less than sterling motivations. “The Intruder”, is a perennially favorite story in which he describes taking over the fishing hole to which another man once introduced him, and with the years, slowly coming to regard it as his own jealously guarded private domain. With the passage of decades and advancing physical infirmities he found it; “expedient to locate and hack out a series of abandoned old logging roads to let myself drive within easier walking distance of my secret spot…the low cunning of middle age was replacing the hot stamina of youth”… It is the admission of human frailty and self-centeredness that makes the story all the more moving, when he eventually encounters the now crippled and aging man, whom we are left to assume was a war veteran – the one who had once introduced him to this honey-hole on the Escanaba River. The writer describes his own uncharitable behavior towards the intruder - his slowness to recognize him or pick up on the hints he drops. A self-satisfied moralist could not have communicated what John did with that story.

There is something very compelling about the way John operated and expressed himself. It comes from another time period, one that favored more understated passions, and one which, to my ear, seems to have demanded more superficial conformity in dress and manners, but which ultimately allowed more room for actual individualism. But all such speculations about greater freedom and better fishing in the good old days aside, there was something very masculine about his pleasures that draws me to this literature depicting with sympathy the company of men he kept around his interests in fishing, mushrooming, drinking, his clubhouse, barroom and cards. Society then appears to have been far more gender segregated than it is today, but by then also a lot more domesticated than it had been in his father’s generation, when there’d still been a frontier and wilderness to tame, rather then the last vestiges of fast disappearing wilderness requiring our protection. He needed to live the life about which he wrote. I doubt the sanitized and domesticated fictional man, reinvented after his death - attending PTA meetings and church services instead of sneaking out fishing, could have written the books for which I value him.

So finally the question arises; do these offending etchings mean much and are they at all accurate. I saw him for only two days, but I really don’t think one’s visage conceals one’s way of life very effectively from those of us who are used to looking for the tracks and signs that are used to create a convincing drawing. What you fill your days with is who you are and it leaves indelible traceries of scars, frown lines, wrinkles and creases which we are all very accustomed to mining for meaning from the day we are born until the day we die. I also doubt that a weak portrayal could have elicited such excitement and resistance. Twenty years later, these portraits are still controversial (in admittedly limited and increasingly diminishing circles), but as I look at them again and reflect upon these two intervening decades, I find they still hold up well enough to reprint them and to make into this long-delayed folio. They do justice to my memory of a meaningful meeting with a fine elder, distant mentor and today, a deceased colleague. I could have done worse.

Ladislav R. Hanka

Kalamazoo 2010

Voelker’s camp at Frenchman’s Pond

Frenchman’s Pond from a casting platform with totemic scuplture

John Voelker,

photographed in native habitat in the Rainbow Room Bar...

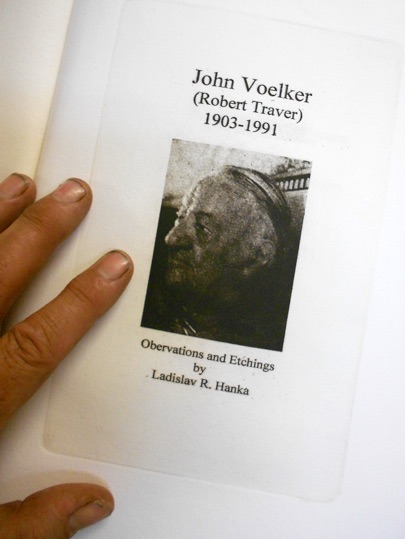

Portrait of a Trout Fisherman and Writer of Fine Fishing Stories

John Voelker

(Robert Traver)

1903- 1991

Letter from the judge, in answer to my having sent him some proofs and a discussion of my intentions - done in his characteristic green felt pen on tastefully venomous yellow legal pad

The End

....and his visage snatched from the bar, scritched into copper and his mug embalmed in ink & Paper –

ready of course, to be interred in a case of beer ,. emblazoned with pride on each and every bottle of that wondrous fisherman’s ambrosia, the day that the honorous prohibition is once again lifted.